2025 June 24;6(6):784-791. doi: 10.37871/jbres2131.

An Evidence-Based Hypothesis: Doctors Do Not Make Decisions Randomly But Based on Individual Patient's Risk Profiles

Franz P1*, Christel W2 and Manfred W3

2Universität Heidelberg / Campus Mannheim, Abt. Medizin. Statistik, 68167 Mannheim, Germany

3Universitätsklinikum Ulm, Klinik für Anästhesiologie und Intensivmedizin, 89081 Ulm, Germany

According to Sir Archibald Cochrane systematic errors can be avoided in clinical studies if the three dimensions of health care are confirmed: (a) “efficacy”, the objective principle of action (we named “Proof of Principle, PoP”) (b) “effectiveness” the objective suitability in everyday care (also described as the Real-World Effectiveness, RWE), and (c) the subjectively perceived value (Value). The strategy for confirming these three dimensions is suggested. The method for proving the suitability of health services in everyday care (RWE) is described in six chapters: 1. The basis for the evaluation of health services. 2. The "terminology conflict" used to describe the "natural chaos in everyday care". 3. The proposed solution to prove suitability for everyday use. 4. The method for detecting everyday effects of health care. 5. The importance of emotionally perceived information. 6. Goals that can only be achieved in Pragmatic, not Randomized Trials.

If the hypothesis that physicians base their decisions on the risk profile of the individual patient is accepted, medicine can take a significant step forward. This step brings about a change of perspectives. Decisions for (non-experimental) day-to-day care are no longer derived from experiments but from (pragmatic) controlled observations of everyday care.

The Basis for Evaluating Health Performance

Nearly 100 years ago, Sir Archibald Cochrane called for answers to three questions to describe the suitability of health services: "Can it work?”, “Does it work?”, “Is it worth it?" [1]. Table 1 describes a strategy which identifies the three dimensions of the different responses, the different study conditions, the perspectives, the forms (structures) and functions, and the measurement methods by which the three results can be distinguished from each other. The methods for answering the first question ("Can it work?") and answering the third question ("Is it worth it?") have been developed. So far, however, there is no accepted method with which the second question ("Does it work?") can be answered.

| Table 1: Three-dimensional strategy for description of Proof of Principle (PoP), Real-World Effectiveness (RWE), and Value, i.e. the three answers to the three questions of Sir Archibald Cochrane. Non-exp. RWC: Non-experimental Real-World Condition. Preliminary versions of this table have been published [2-5,20]. | |||

| Cochrane questions | Can it work? | Does it work? | Is it worth it? |

| Outcome dimensions |

Efficacy or Proof of Principle (objective PoP) |

Real-World Effective-ness (objective RWE) | Value individual or societal (subjective) |

| Study conditions | Experimental study condition (ESC) |

Non-exp., RWC with systematic evaluation of data | Non-exp., RWC without systematic but individual evaluation of data |

| Perspectives | Clinical Research | Health services research | Economic Research |

| Forms (structures) | Explanatory or interventional study |

Pragmatic or observational study | Complete economic analysis |

| Functions | Demonstration of Proof of Principle | Confirmation of Real-Word Effectiveness | Comparison of costs and consequences |

| Tool | Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) | Pragmatic Controlled Trial (PCT) | Cost Effectiveness Analysis |

These three answers describe a) the experimental and objective proof of Proof of Principle (PoP) and the two non-experimental proofs, b) objective Real-World Effectiveness (RWE), and c) subjectively perceived value (VAL). Acronyms are clarified in table 1.

The Terminology Conflict to Describe the "Natural Chaos In Everyday Care"

Since Sir A. Cochrane's request, it has not yet been possible to find a suitable method for answering the second Cochrane question ("Does it work?). Solving this challenge is not trivial for three reasons.

- On the one hand, there are many different health risks. Only a few patents pose a singular health risk. Most of all patients differ from other patients by their individual health risk profile.

- Every conscientious physician bases his care strategy on the current health risk profile of his individual patient.

- Given the large number of different risk profiles, it is plausible that it is almost impossible to recommend uniform care strategies for the different risk profiles.

In day-to-day care, various endpoints of care must be considered, e.g. the achievement of the main goal criterion, the avoidance of side effects and the avoidance of unnecessary costs. These three challenges cannot be solved with an experimental RCT because:

- In day-to-day care, various endpoints of care must always be taken into account, e.g. the achievement of the main goal criterion, the avoidance of side effects and the avoidance of unnecessary costs. The methodological limitations of an experimental study allow only the valid measurement of a singular primary endpoint. The responses to all other outcomes measured in an RCT can be used as a hypothesis for confirmation in a subsequent RCT.

- An RCT can only include a highly selected subgroup of patients. These patients must not meet exclusion criteria, i.e., risks that would distort the measurement of the primary endpoint. The patients need to be invited by a doctor to participate in an RCT and need to accept this invitation. These three factors illustrate the difficulty of distinguishing the risk profiles of all patients who ask for solving a particular healthcare problem from the risk profiles of patients who will be included in an RCT.

- These three selection factors explain why an RCT cannot describe the risk profile of the population studied in an RCT. This limitation explains why an RCT can only answer the first Cochrane question, the PoP, but not the second Cochrane question, the RWE of the investigated intervention.

- Although an RCT evenly distributes patients into subgroups, it usually does not describe the risk profiles of these randomized subgroups. Consequently, the results of an RCT describe only average risk profiles of patients in the randomized subgroups. The risk profile that characterizes the subgroup of patients who benefit most from therapy cannot therefore be identified in most RCTs.

A summary of the most important philosophical arguments questioning the validity of the results of RCTs was described [6,7]. At first, proving the suitability of health services for everyday use seemed to be unsolvable. That's why, about 30 years ago, a group of dedicated scientists convinced us all that the experimental method of the Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) was the only tool that could be used to describe health care outcomes in an unbiased way. The inconsistency of form and function of this statement raised doubts about its validity [8]. A structured experiment such as the RCT is unsuitable for describing effects that arise under the conditions of unstructured everyday care for three reasons:

- If care does not take place under the conditions of "natural chaos in everyday care", i.e. if it is based on the (entire) risk profile of the individual patient, the RWE cannot be measured.

- Almost every patient differs from other patients due to his or her individual risk profile.

- Every doctor who works diligently captures the entire risk profile of his patient before developing his individual care strategy, personalized medicine, for his patient.

At the end of the 1990s, Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) gave us all the (unfortunate) impression that most of all medical decisions are subjectively justified because they have not yet been made based on a universally valid strategy [9]. This assumption is based on a common bias described by Altman and Bland: "Absence of evidence is not evidence" of absence" [10]. The method doctor’s use for their decision-making was just unknown in the 1990s. In retrospect, the demand at the time to confirm the detection of the PoP and the proof of RWE by means of an experiment is not scientifically sound. The evidence of the inconsistency of form and function of the terminology used has confirmed the existing doubt that an experimental study design can hardly be suitable for proving both the (experimental) PoP and the (pragmatic) RWE [8]. 30 years later, we were able to offer a plausible and scientifically supported proposal to solve the problem.

The Proposed Solution for Proving Suitability for Everyday Use

We are a group of German scientists from different professions who have been trying to prove the effects that are generated under the conditions of "natural chaos in everyday care" [9]. For this proof, we were able to fall back on three valuable clues from our city of Ulm ("the Ulm heritage"). Albert Einstein (*1879 in Ulm, Germany) pointed out that "a problem cannot be solved with the mindset that caused this problem". We have strictly adhered to this advice not to fall back into traditional ways of thinking when developing our solution. Two additional hints were obtained from the former teachers and students of the "Ulm Academy of Design (Hochschule Für Gestaltung HFG)". We got to know the rule of the American designers and architects "Form Follows Function" [1] and, as a unique selling point of the Ulm HFG, the formulation of the requirements of the profession of designers and architects to also consider socially relevant aspects of the products and concepts produced [11]. By applying the FFF rule to international methodological rules for proving the suitability of health care lines for everyday use, we have encountered a contradiction, the lack of correspondence between form and function, which is addressed as the core of the present commentary. This is a significant social problem, because the currently used method for proving the suitability of health services for everyday use needs to be questioned. In doing so, we have joined forces with the designers of the HFG. The question of proving the suitability of health services for everyday use is not a German problem, but a global one. As German perfectionists, we have learned from experience: "If we Germans do something wrong, we may do it really wrong". That is why we propose the health care concepts we have developed to a discussion with international teams to obtain alternative proposals that contribute to solutions to the challenges addressed.

The Method for Demonstrating Everyday Effects of Health Care

In cooperation with health scientists from the Universidade Federal Fluminense Niteroí / RJ, Brazil, we have mapped the steps that each physician takes to derive the best possible care strategy for his individual patents [12]. In cooperation with health scientists from the Universidade Federal Fluminense Niteroí / RJ, Brazil, we have mapped the steps that each physician takes to derive the best possible care strategy for his individual patents [12]. The results of this study formed the basis for the concept for the detection of everyday effects that occur under the conditions of "natural chaos" of everyday care. To this end, three pieces of information need to be collected from each patient that have so far only been partially recorded:

- The definition of all endpoints that will be measured as success criteria of a Pragmatic Controlled Trial (PCT). As a rule, this is the main objective criterion of the study, the most significant side effects, and the cost of care.

- The description of all health risk factors of all individual patients recruited in this PCT who may influence one of the measured endpoints. The risk profile specific to an endpoint for a patient is referred to as ESRP (endpoint-specific risk profile). These risk profiles will differ for the same patient for each measured endpoint. Without knowledge of the risks, it is impossible to distinguish whether an observed result can be explained by the existing risk profile or by the intervention conducted. The existing risk profiles can only be ruled out as the cause of the observed results if patients with comparable ESRPs have received different interventions.

- Comparable patient groups can be formed for each measured endpoint by defining an algorithm that identifies the risk factors that assign a patient to a high-risk or intermediate or low-risk group specific to each of the measured endpoints. This classification of risk profiles is essential to correctly interpret the results obtained, because each result can be caused either by the intervention administered or by different risk profiles of the populations studied.

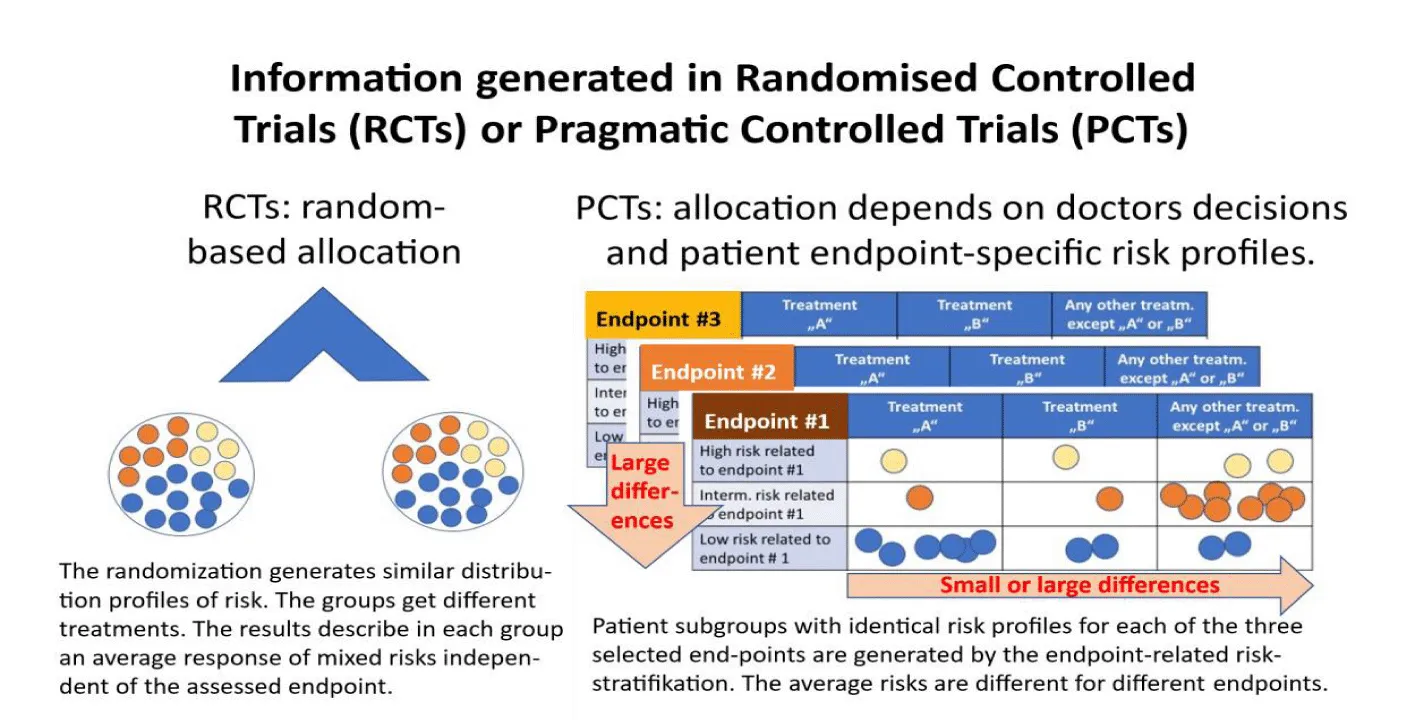

Figure 1: Results generated in experimental RCTs or in pragmatic PCTs. The PCT identifies the individual patients that received a defined treatment “A” or “B” or are listed in the group “any other treatment” when the differences in outcomes of type “A” or type “B” treatment should be compared to the range of outcomes observed in patients of the same risk group who received any other treatment. “A” and “B” may include a single type of treatment or a group of similar treatments. In addition to the treatment the ESRP were used in all patients for stratification in a high-risk (yellow) or intermediate-risk (red) or a low-risk group (blue) patient separately for each of the endpoints. The same patient may be classified to different risk groups depending on the assessed endpoint. Modified from [4,20].

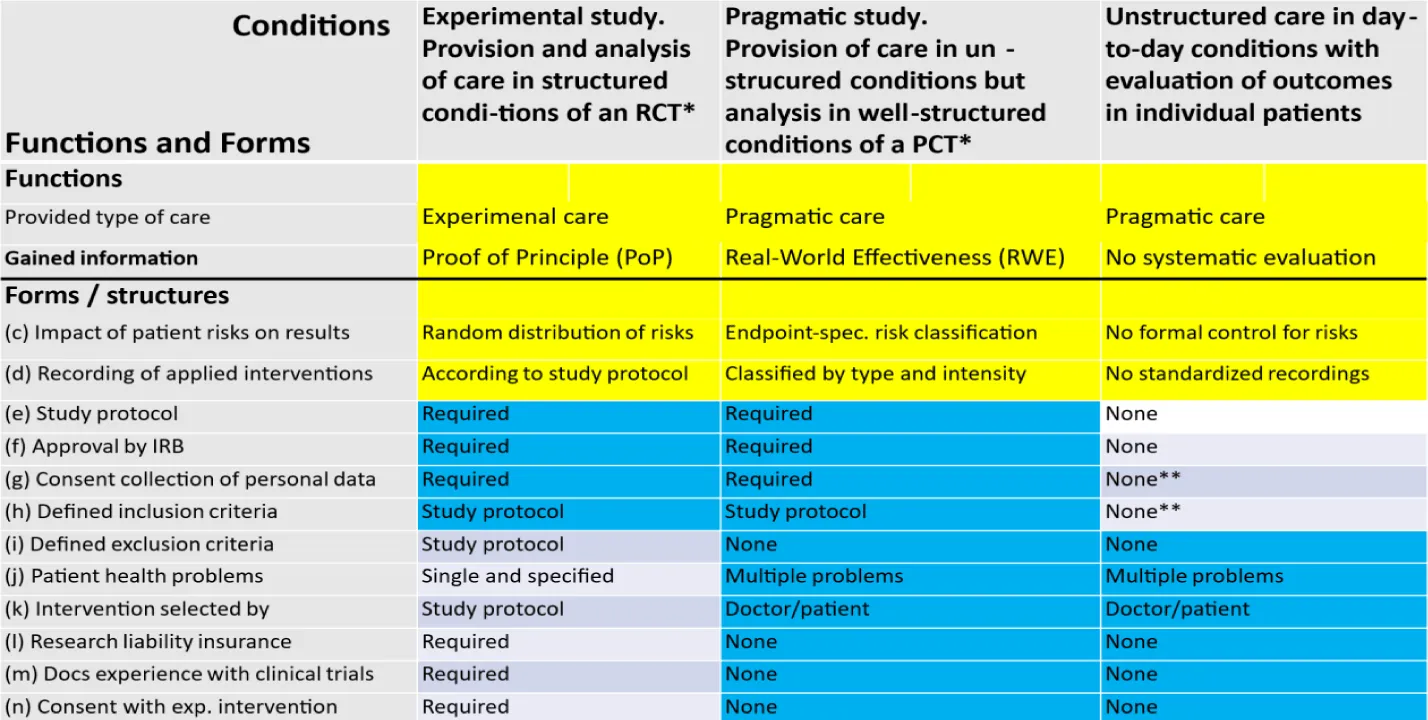

Table 2: The colors in this figure underline the differences between congruent and discordant formal (structural) criteria of the three functionally different conditions of care: Experimental care used in Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) and Pragmatic care used either in Pragmatic Controlled Trials (PCTs) or in the unstructured condition of day-to-day usual care without systematic evaluation of outcomes. Forms and functions that are different in the three conditions of care are indicated by a yellow background. Formal criteria that are identical in two of the three conditions of care are indicated by a blue background. IRB: Institutional Review Board. * RCT: Randomized Controlled Trial. *PCT: Pragmatic Controlled Trial. **None: Conditions defined in the doctor-patient contract.

The care under the conditions of a Pragmatic Study (Table 2) enables the care of patients under the usual conditions of everyday care combined with an observed (descriptive) analysis of all existing risks that may influence the measured outcomes (ESRPs). By taking these risks into account, it is possible to distinguish which of the results are due to different initial risks and which are due to different interventions. Due to insufficient data, the usual (pragmatic) care under everyday conditions, outside of a study (Table 2), does not allow for a systematic evaluation of all care outcomes. Nevertheless, individual comparisons can be made on the same patient before / after an intervention.

The Importance of Subjective Decisions

The subjective decisions based on emotional perceptions are anchored in the theory of EBM but have almost no significance in the practical implementation. David Sackett emphasizes that both components, the (objective) external and the (subjective) internal evidence, must be included in decision-making, but does not discuss their effect on decision-making. On an empirical basis, it can be shown that "perceived security" is to be understood as a subjective perception of objective risks. The difference between objective risk and its subjective perception can be explained by intermediary communication [13].

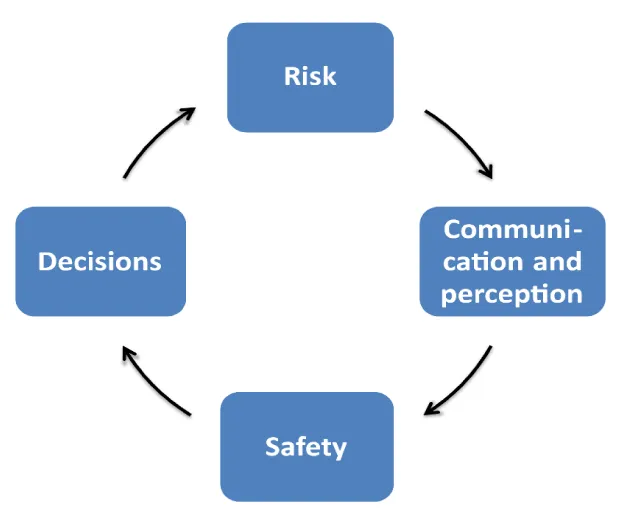

Figure 2: The safety loop describes the relationship of objective risks and its subjective perception mediated by the type of communication. The communication of “bad news” can considerably reduce the “perceived safety” while the effects of the communication of “good news” have only rarely detectable effects [13,14]. The effect of communication, which can significantly increase the subjective perception of objective risks, can be quantified. According to our data, the subjective perception of objective risks, the "perceived safety", can be significantly impaired by "bad news" but can hardly be influenced by the communication of "good news" [14]. Due to the considerable risk of influencing decision-makers at all levels of a society and almost unlimited population groups with simple messages, this topic requires an interdisciplinary approach.

Goals that Can Only be Achieved in Pragmatic, Not Randomized, Trials

Three goals can only be achieved with pragmatic PCTs, but not with experimental RCTs: 1. the demonstration of the social value of health services, 2. the comparison of the outcomes of patient populations with similar risk profiles, and 3. the reduction of time and cost by combining care and research.

Demonstrate the social value of health services

- RCTs cannot include patients with confounding factors (defined as exclusion criteria). However, many physicians do not (for various reasons) invite suitable patients to participate in an RCT, and not all patients who have been invited to participate in an RCT will accept this invitation. Consequently, RCTs compare only small subgroups of highly selected patients.

- RCTs cannot include patients with confounding factors (defined as exclusion criteria). However, many physicians do not (for various reasons) invite suitable patients to participate in an RCT, and not all patients who have been invited to participate in an RCT will accept this invitation. Consequently, RCTs can examine only small subgroups of highly selected patients.

- RCTs can evaluate only the outcomes of the primary endpoint, but not multiple endpoints that are equally important for clinical decisions, such as the main endpoint, side effects, and costs.

- RCTs can evenly distribute the different risk profiles of the study populations to all included subgroups of the overall study population. However, it is not possible (in most RCTs) to provide information on the risk profiles presented within the subgroups studied. Therefore, most RCTs lack external validity. RCTs can only guarantee internal validity if an unaffected randomization of all subjects was possible.

- RCTs describe a single result for each of the included subpopulations. However, each of these subpopulations includes patients with different risk profiles. While these risk profiles are similarly distributed across all included subgroups, their details are usually not analyzed. Consequently, the results described represent an average result of all included risk groups. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn about individual patients with different risk profiles.

- This RCT result is sufficient to confirm the proof of principle of a new intervention, but not to confirm the Real-World Effectiveness (RWE). The RWE of a new intervention for any endpoint requires the knowledge of each patient's "Endpoint-Specific Risk Profiles (ESRPs)" and "Endpoint-Specific Risk Class (ESRCs)", as the results observed in each study vary from the type of intervention and the risk profiles of the treated patients. RCTs do not consider the ESRPs of individual patients. Therefore, RCTs have no external validity and cannot predict response to interventions without knowing the ESRPs of all patients included in an RCT.

- RCTs provide only the response of the highly selected subgroups of patients to the primary endpoint studied. Clinical decisions typically require answers to multiple outcomes.

- The results of RCTs are often combined in reviews, health-technology assessments and metanalyses, without knowing the ESRPs of the enrolled patients. This potential bias was already recognized 20 years ago [15], but has it been included in the public discussion only recently [16-18].

Comparison of the results of patient populations with similar risk profiles

- RCTs, the results of which are summarized in reviews, meta-analyses or HTA reports, without knowing the risk profiles of the subjects studied, can be explained either by the different interventions or by different risk profiles of the study populations.

- Therefore, the validity of the results of these synopses will be higher if the ESRPs of the patients studied are taken into account in addition to the interventions.

Reduction of time and cost by combining care and research

- A few positive RCTs are sufficient to detect PoP and reduce the time and cost of development.

- The early start of daily care combined with health services research after confirmation of the PoP saves time and money.

- Ultimately, the coupling of care and research in a joint project justifies the distribution of the costs for both on different shoulders (private and public).

In summary, we use this perspective to describe the strategic considerations that have been able to mature over the course of 30 years to replace some brittle linchpins of the EBM with robust columns. The first important reflections on the heterogeneity in systematic reviews were discussed by Glasziou in 2002 [15]. We first mentioned the concept of ESRPs in a health policy interview in 1917 [19], and Kraus described logical discrepancies with the concept of RCTs from a philosophical perspective in 2018 [6,7]. An analysis of medical decisions discusses significant aspects [21]. Our proposal to consider the ESRPs could help optimize patient non-adherence and the optimal solution for individual patients. These considerations will probably be accompanied by resistance, just like the considerations made about 30 years ago by David Sacket and his team on the development of evidence-based medicine. These resistances are part of the development of a social consensus. The process could be accelerated if we succeeded in presenting the desired goals in such a way that they can be perceived emotionally, not just rationally, by those affected. We all can only make far-reaching decisions if our subjective values coincide with rational considerations.

Contributions

FP developed the concept and prepared the manuscript. ChW and MW are contributing since 20 years to the development and robustness of the concept.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors must report any conflict of interest.

Support

This project did not receive external support.

References

- Sullivan LH. The tall office building artistically considered. Lippincott’s Magazine. 1896;57:403-409.

- Haynes B. Can it work? Does it work? Is it worth it? The testing of healthcareinterventions is evolving. BMJ. 1999 Sep 11;319(7211):652-3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.652. PMID: 10480802; PMCID: PMC1116525.

- Porzsolt F, Eisemann M, Habs M, Wyer P. Form follows function: pragmatic controlled trials (PCTs) have to answer different questions and require different designs than randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Z Gesundh Wiss. 2013 Jun;21(3):307-313. doi: 10.1007/s10389-012-0544-5. Epub 2012 Nov 7. PMID: 23687408; PMCID: PMC3655212.

- Porzsolt F, Weiss Ch, Weiss M, Müller AG, Becker SI, Eisemann M, Kaplan RM. Versorgungsforschung braucht dreidímensionale Standards zur Beschreibung von Gesundheitsleistungen [Health services research needs three-dimensional standards for description of health services]. Monitor Versorgungsforschung. 2019;04:53-60. doi: 10.24945/MVF.04.19.1866-0533.2163.

- Porzsolt F, Weiss Ch, Weiss M, Jauch K-W, Kaplan RM. Demystification – A solution for assessment of real-world effectiveness? Trends Med. 2020;20:1-2 doi: 10.15761/TiM.1000231

- Krauss A. Why all randomised controlled trials produce biased results. Ann Med. 2018 Jun;50(4):312-322. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2018.1453233. Epub 2018 Apr 4. Erratum in: Ann Med. 2018 Nov;50(7):634-635. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2018.1519954. PMID: 29616838.

- Krauss A. Assessing the overall validity of randomised controlled trials. International Studies in the Philosophy of Science. 2021;34:159-182. doi: 10.1080/02698595.2021.2002676.

- Porzsolt F, Wiedemann F, Phlippen M, Weiss C, Weiss M, Schmaling K, Kaplan RM. The terminology conflict on efficacy and effectiveness in healthcare. J Comp Eff Res. 2020 Dec;9(17):1171-1178. doi: 10.2217/cer-2020-0149. Epub 2020 Dec 14. PMID: 33314965.

- Porzsolt F, Weiss Ch, Weiss M. Covid-19: Twinmethode zum nachweis der real-world effectiveness unter Alltagsbedingungen [Covid-19: Twin method for demonstration of Real-World Effectiveness (RWE) under the conditions of day-to-day care]. Das Gesundheitswesen. 2022;84:1-4. doi: 10.1055/a-1819-6237.

- Altman DG, Bland JM. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. BMJ. 1995;311(7003):485. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7003.485.

- Spitz R. Stiftung Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG). Ulm Nov. 2012.

- Porzsolt F, Rocha NG, Toledo-Arruda AC, Thomaz TG, Moraes C, Bessa-Guerra TR, Leão M, Migowski A, Araujo da Silva AR, Weiss C. Efficacy and effectiveness trials have different goals, use different tools, and generate different messages. Pragmat Obs Res. 2015 Nov 4;6:47-54. doi: 10.2147/POR.S89946. Erratum in: Pragmat Obs Res. 2016 Jan 12;7:1. doi: 10.2147/POR.S100784. PMID: 27774032; PMCID: PMC5045025.

- Porzsolt F. Safety means perception of risk. J Med Safety. 2016;10:18-24.

- Porzsolt F, Pfuhl G, Kaplan RM, Eisemann M. Covid-19 pandemic lessons: uncritical communication of test results can induce more harm than benefit and raises questions on standardized quality criteria for communication and liability. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2021 Sep 21;9(1):818-829. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2021.1979407. PMID: 34567838; PMCID: PMC8462930.

- Glasziou PP, Sanders SL. Investigating causes of heterogeneity in systematic reviews. Stat Med. 2002 Jun 15;21(11):1503-11. doi: 10.1002/sim.1183. PMID: 12111916.

- Lee S, Khan T, Grindlay D, Karantana A. Registration and Outcome-Reporting Bias in Randomized Controlled Trials of Distal Radial Fracture Treatment. JB JS Open Access. 2018 Jul 24;3(3):e0065. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.OA.17.00065. PMID: 30533597; PMCID: PMC6242325.

- Cook C, Garcia AN. Post-randomization bias. J Man Manip Ther. 2020;28:69-71. doi: 10.1080/10669817.2020.1739153. PMID: 32242772; PMCID: PMC7170305.

- Fouche PF, Stein C, Nichols M, Meadley B, Bendall JC, Smith K, Anderson D, Doi SA. Tranexamic Acid for Traumatic Injury in the Emergency Setting: A Systematic Review and Bias-Adjusted Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann Emerg Med. 2024 May;83(5):435-445. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2023.10.004. Epub 2023 Nov 22. PMID: 37999653.

- Stegmaier P. Externe evidenz ist genauso wichtig wie interne. Monitor Versorgungsforschung. 2017;3:10-15. doi: 10.24945/MVF.03.17.1866-0533.2013.

- Porzsolt F, Weiss M, Weiss Ch. Applying the rule of designers and architects “Form Follows Function (FFF)” can reduce misinterpretations and methodical shortcomings in healthcare. Trends Gen Med. 2024;2(1):1-7.

- Irvine A, van der Pol M, Phimister E. Doctor decision making with time inconsistent patients. Soc Sci Med. 2022 Sep;308:115228. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115228. Epub 2022 Jul 20. PMID: 35926445.

Content Alerts

SignUp to our

Content alerts.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.