Medicine Group 2025 May 12;6(5):433-438. doi: 10.37871/jbres2100.

Autologous Angiogenic Cell Precursors- A Molecular Strategy for the Treatment of Heart Failure: Response to Biocardia’s Cardiamp HF Trial

Fraser C Henderson1-3*, Kelly Tuchman3 and Ina Sarel4

2Hemostemix Inc., Toronto, Ontario, Canada

3Metropolitan Neurosurgery Group, Maryland, USA

4NurExone Biologic Inc., Haifa, Israel

Introduction

Stem cell therapy for the treatment of heart failure in patients not adequately responding to optimized heart failure medication is currently being studied in clinical trials, with the hope of improved heart function and quality of life. BioCardia was granted FDA Breakthrough Designation for its Phase III trial of CardiAMP® Cell Therapy for the treatment of Heart Failure with reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF). Unfortunately, BioCardia’s phase 3 trial one-year follow-up failed to reach its endpoint, which has dampened enthusiasm for HFrEF stem cell treatment. The CardiAMP-HF Trial studied 125 ischemic heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction enrolled at 18 centers in the United States and Canada. All patients were maintained on heart failure medication, the treatment group receiving a single dose of CardiAMP Cell Therapy - autologous bone marrow cells delivered by transcatheter, intracoronary technique. The primary endpoint of the study - the all-cause of death, including cardiac death equivalents- failed to show any benefit. The treated group reported a 5.6% rate of all-cause death and cardiac death equivalents after one year, compared to 5.3% in the control group. Moreover, nonfatal major adverse cardiac events were similar in the two cohorts, with 16.7% in the treatment group versus 15.8% in the control, and there was no difference between the two groups in the Six-Minute Walk test distance. BioCardia concluded that the current phase III study was unlikely to succeed, given the failure of the bone marrow cell therapy to significantly improve outcomes on any aspect of the composite endpoint of the trial.

However, subgroup analysis of those patients with elevated Brain derived Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) showed decreased mortality and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events, improved quality of life, a modest improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction, and an improvement in the Six Minute Walk Distance. In a not surprising turn, BioCardia has initiated patient enrollment for a CardiAMP HF II Study. The new study will focus on the subgroup of patients suffering from active heart stress (those with elevated NT-proBNP biomarker). BioCardia’s trial illustrates the primary importance of selecting the subpopulation of cardiomyopathy patients likely to respond favorably to stem cell therapy. The Biocardia study showed more significant improvement in patients with elevated BNP biomarkers. BNP occurs in response to increased ventricular wall strain and to volume overload, and elevations of BNP characterize up to 90% of patients with Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM).

As the most common form of non‐ischemic cardiomyopathy worldwide, DCM may be a more favorable candidate population for stem cell therapy. With an estimated prevalence of 1 in 2500 persons, DCM is defined by dysfunction of the left or both left and right ventricles, with dilation of the ventricular walls. The prognosis is extremely poor. DCM is a leading cause of the need for heart transplantation in adults [1]. Despite improved medical treatment, there is a trend towards worsening of left ventricular function [2]. Systematic reviews have demonstrated beneficial therapeutic effects of adult bone marrow-derived stem cells for non-ischemic DCM, in terms of improved systolic function and mortality [3,4]. Other reviews report improvement of left ventricular ejection fraction, end systolic and end diastolic volume in DCM, but caution that the ultimate clinical implications of these improvements are uncertain [5-7]. There have been no concerns as to the safety of stem cell treatments [8,9].

The histopathology of DCM is a prototypical inflammatory condition, manifesting the full spectrum of immune response. Both resident and recruited inflammatory cells- including macrophages, dendritic cells, granulocytes, B and T cells, and NK cells - release cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-18, IFN-γ, and TNF-β-promoting a remodeling of the extracellular matrix, collagen deposition, impaired contractility, damaged endothelial function and left ventricular enlargement. Cardiomyocyte injury and the immune cascade that follows ischemia reperfusion injury result in the infiltration of inflammatory cell populations, scar formation, fibrosis and a post-procedure death rate of 7-15% [10]. The development of DCM may result from chronic progressive inflammatory response that leads to remodeling of myocardial tissue and fibrosis due to autoimmune disease and viral myocarditis [11].

The important unanswered question in the BioCardia study is whether the molecular biology of the stem cell type is optimal for the specific pathophysiology being treated. There remains a lack of clarity regarding the relative efficacy of cell type, donor origin, or patient selection in terms of the chronicity of ischemia or the type of cardiomyopathy. Specific attributes of the molecular biology of one cell type might a priori suggest improved efficacy. Some cell types might be optimal for the treatment of conditions with underlying inflammation, ischemia, and fibrosis.

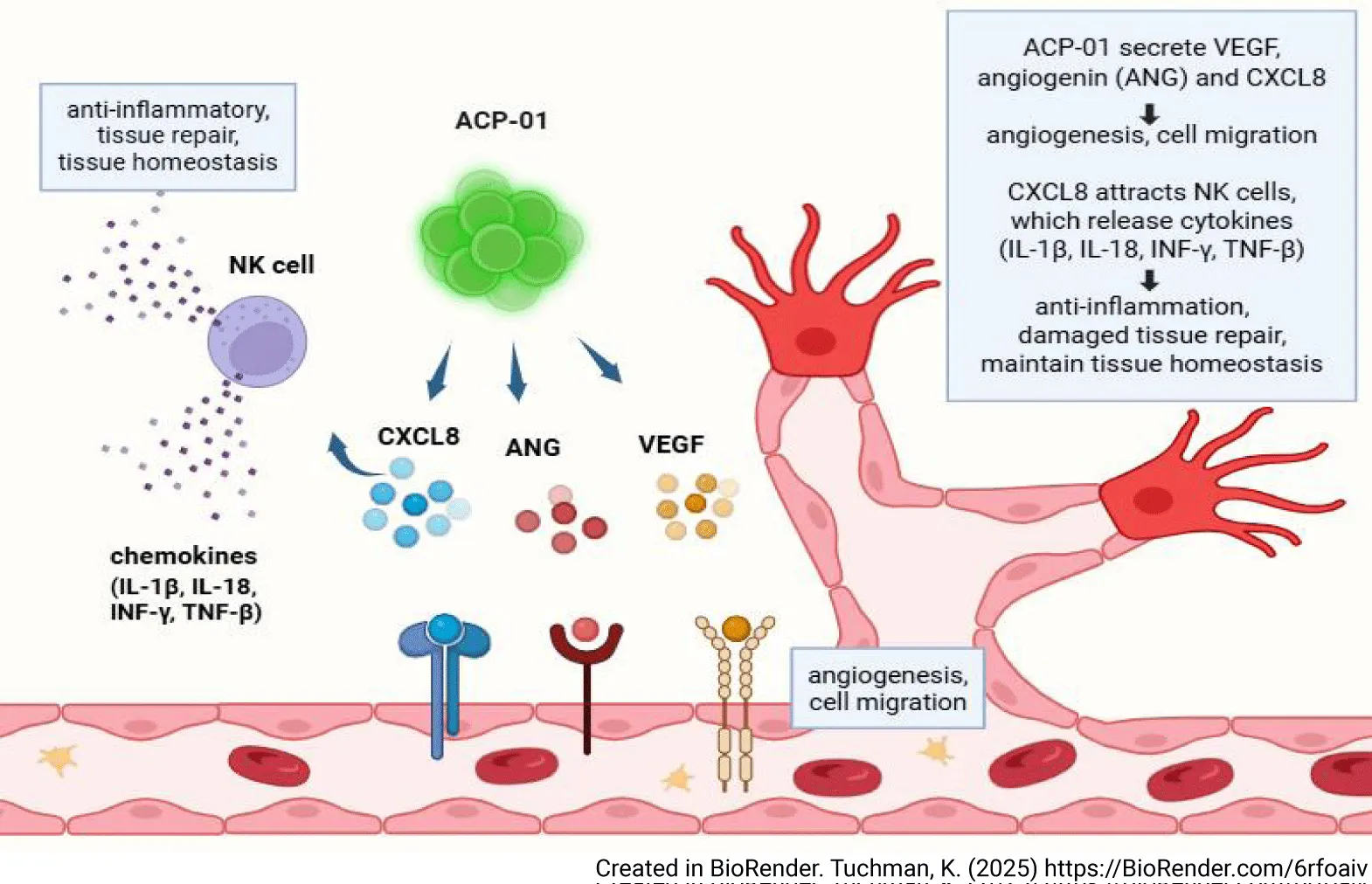

Decreasing cardiac fibrosis by CXCL8 attraction of NK cells

Angiogenic precursor cells (ACP-01 cells, Hemostemix Corp), are peripheral blood derived angiogenic progenitor cells offering a compelling treatment of inflammatory disorders such as DCM through attraction of Natural Killer (NK) cells (Figure 1). ACP-01 express high levels of CXCL8 [5], which exhibits chemokine activity toward spatially distant NK cells [12]; the CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors on NK cells are highly specific to the ligand chemokine CXCL8 [13]. NK cells are a part of the innate lymphoid cell (ILC) population. NK cells stifle collagen production in cardiac fibroblasts, and inhibit the assembly of inflammatory cells in the heart [14]. Suppression of NK cells is associated with DCM. When NK cells are depleted, cardiac eosinophil infiltration occurs. NK-derived IFN-γ decreases the deleterious effect of eosinophils on the myocardium by reducing local eotaxin concentrations, and reducing the ability of eosinophils to migrate to the heart. NK cells isolated from healthy human peripheral blood induce the activation and apoptosis of eosinophils, and prevent the accumulation of certain inflammatory populations in the heart. NK cell infiltration into the myocardium is maximal at 7 days after ischemic injury and militates against cardiac fibrosis by limiting collagen formation in cardiac fibroblasts [14,15].

NK cells expressing IFNγ and other mediators create an anti-inflammatory environment, limiting fibrosis through down regulation of eosinophils and other pro-fibrotic cell types. Murine studies have demonstrated reduction in cardiac myocyte apoptosis and collagen formation, and increase in neovascularization due to expansion of NK cells after bone marrow cell transfers to the heart following myocardial infarct [16].

DCM may result from a viral infection. Serving in the first line of defense against many intracellular pathogens, NK cells prevent viral replication by detecting and destroying infected resident cells. NK cells suppress inflammation through modulation of immune cell physiology directly through receptor-ligand interactions, and indirectly by cytokine secretion. NK cells are responsible for the initial production of type I interferons, such as IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ, which initiate the anti-viral inflammatory cascade, and suppress release of T Helper 2 (Th-2) cytokines, decreasing inflammation [11]. NK cell cytokine release may affect alteration of T Helper subtypes, direct contact-mediated lysis of auto-aggressive T cells, and accelerate maturation of monocytes and dendritic cells [17,18]. Through their ability to produce IFNγ and express the transcription factor T-bet, NK cells are important in maintenance of tissue homeostasis [19]. ACP-01 attract NK cells to the sites of repair and thus modulate the immune inflammatory response to injury.

Angiogenesis

The molecular biology of ACP-01 optimizes microcirculation through angiogenesis. ACP-01 are specifically programmed to form endothelial cells and tube-like structures, and to express tissue regeneration factors VEGF and angiogenin, which promote angiogenesis [20]. ACP-01, through expression of high levels of CXCL8, enhance angiogenesis through Ras-MAPK/PI3K activation and the AP-1/NF-kB axis, promoting the proliferation, growth, and viability of vascular endothelial cells [5,21-23].

ACP-01include cells with the CD34 + surface cell marker. CD34+ stromal cells are essential to angiogenesis, participating in cell migration, control and organization of the extracellular matrix, scaffolding, immunomodulation, neurotransmission, control and regulation of other cell types and regeneration [24]. Sprouting angiogenesis requires migration of endothelial cells, alteration of the extracellular matrix, proliferation of endothelial cells and mobilization of the perivascular CD34+Stem Cells. The CD34+ stem cells in ACP-01 are of primary importance in the process of angiogenesis and improved microcirculation [25,26]. However, ACP-01 increased expression of CXCL8 results in mobilization of peripheral CD34+ precursor cells to amplify the angiogenic response [27]. Improved microcirculation minimizes the area of ischemic myocardium, rescuing penumbra and lessening dysfunctional macroscopic remodeling of the surrounding non-ischemic myocardium [28,29].

Autologous cells are not subject to cell-to-cell interactions

As an autologous treatment, ACP-01 are not subject to cell-to-cell interactions [30,31], MHC incompatibilities, or immune rejection from alloreactive antibodies [32]. Moreover, autologous hematopoietic derived stem cells – such as ACP-01- have more prolonged survival than allogeneic cells [33]. The production and sorting method of highly specific hematopoietic progenitor cells, such as autologous ACP-01, results in fewer of the heterogeneous cell populations, which can negatively affect therapeutic results [34]. Fresh autologous cells may be more effective than stored cells [35].

Cell Migration

Finally, ACP-01 minimize ischemic injury to the myocardium through cell migration. Endothelial cell precursors express high levels of CXCR4, which is strongly attracted to chemokines released from injured or ischemic tissue, specifically the CXCL12 chemokine. This CXCR4/CXCL12 axis results in robust migration and embedding of transplanted ACP-01 into injured myocardium [36]. Continuous passage of mesenchymal stem cells during preparation may result in decreased expression of chemokine receptors CXCR2/4; on the other hand, the ACP-01 do not undergo division and multiplication during preparation, the consequence of which is increased demonstration of high expression of CXCR4 receptors [37] and increased homing ability [36]. Embedded ACP-01 support tissue survival through paracrine effect.

Conclusion

Failure of large randomized, multi-institutional studies may be due to the inability to select the appropriate subgroup of patients who are most likely to benefit from stem cell treatment, and from failure to select the optimal stem cell for the specific pathology. Hematopoietic derived stem cells, such as ACP-01, which include the subpopulation of CD34+ cells, are programmed for angiogenesis. Expression of high levels of CXCL8 is of particular importance, moreover, in the attraction of immunomodulatory NK cells, and their ability to inhibit inflammation and stromal fibrosis. These characteristics, and the homing qualities of the ACP-01, contribute to the consistently demonstrated significant improvements of cardiac function in patients treated with ACP-01 [5,38]. Based upon the excellent results previously published on a cohort of patients treated with ACP-01 for cardiomyopathy [5]; Hemostemix is presently planning a phase 1 clinical trial for non-ischemic DCM.

Author Contributions

Professor Fraser Henderson Sr conceived, wrote and edited the manuscript. Kelly Tuchman formatted figure 1 and participated in writing and editing the manuscript. Dr. Ina Sarel participated in writing and editing the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

Professor Henderson is a practicing, academic neurosurgeon who serves as Chief Medical Officer, and has stock in Hemostemix, Inc. Kelly Tuchman was paid for her work by Hemostemix Inc. Dr. Ina Sarel was the Chief Scientific Officer for Hemostemix Inc. and has stock in the corporation. She is currently head of CMC, Quality and Regulation at NeurExone Biologic, Inc. Potential conflicts of interest have been transparently disclosed , and do not undermine the scientific validity of the work.

References

- Hershberger RE, Hedges DJ, Morales A. Dilated cardiomyopathy: the complexity of a diverse genetic architecture. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013 Sep;10(9):531-47. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.105. Epub 2013 Jul 30. PMID: 23900355.

- Merlo M, Stolfo D, Anzini M, Negri F, Pinamonti B, Barbati G, Ramani F, Lenarda AD, Sinagra G. Persistent recovery of normal left ventricular function and dimension in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy during long-term follow-up: does real healing exist? J Am Heart Assoc. 2015 Jan 13;4(1):e001504. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000570. PMID: 25587018; PMCID: PMC4330074.

- Lu Y, Wang Y, Lin M, Zhou J, Wang Z, Jiang M, He B. A systematic review of randomised controlled trials examining the therapeutic effects of adult bone marrow-derived stem cells for non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016 Dec 9;7(1):186. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0441-x. PMID: 27938412; PMCID: PMC5148892.

- Marquis-Gravel G, Stevens LM, Mansour S, Avram R, Noiseux N. Stem cell therapy for the treatment of nonischemic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Cardiol. 2014 Nov;30(11):1378-84. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.03.026. Epub 2014 Mar 25. PMID: 25138483.

- Schubart JR, Zare A, Fernandez-de-Castro RM, Figueroa HR, Sarel I, Tuchman K, Esposito K, Henderson FC, von Schwarz E. Safety and outcomes analysis: transcatheter implantation of autologous angiogenic cell precursors for the treatment of cardiomyopathy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023 Oct 26;14(1):308. doi: 10.1186/s13287-023-03539-6. PMID: 37880753; PMCID: PMC10601268.

- Rong SL, Wang ZK, Zhou XD, Wang XL, Yang ZM, Li B. Efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: a systematic appraisal and meta-analysis. J Transl Med. 2019 Jul 11;17(1):221. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-1966-4. PMID: 31296244; PMCID: PMC6624954.

- Diaz-Navarro R, Urrútia G, Cleland JG, Poloni D, Villagran F, Acosta-Dighero R, Bangdiwala SI, Rada G, Madrid E. Stem cell therapy for dilated cardiomyopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Jul 21;7(7):CD013433. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013433.pub2. PMID: 34286511; PMCID: PMC8406792.

- Menasché P. Cell therapy trials for heart regeneration - lessons learned and future directions. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018 Nov;15(11):659-671. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0013-0. PMID: 29743563.

- Vrtovec B, Poglajen G, Sever M, Zemljic G, Frljak S, Cerar A, Cukjati M, Jaklic M, Cernelc P, Haddad F, Wu JC. Effects of Repetitive Transendocardial CD34+ Cell Transplantation in Patients With Nonischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2018 Jul 20;123(3):389-396. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.312170. Epub 2018 Jun 7. PMID: 29880546.

- Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Myocardial reperfusion injury. N Engl J Med. 2007 Sep 13;357(11):1121-35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071667. PMID: 17855673.

- Wang E, Zhou R, Li T, Hua Y, Zhou K, Li Y, Luo S, An Q. The Molecular Role of Immune Cells in Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023 Jul 5;59(7):1246. doi: 10.3390/medicina59071246. PMID: 37512058; PMCID: PMC10385992.

- Vujanovic L, Ballard W, Thorne SH, Vujanovic NL, Butterfield LH. Adenovirus-engineered human dendritic cells induce natural killer cell chemotaxis via CXCL8/IL-8 and CXCL10/IP-10. Oncoimmunology. 2012 Jul 1;1(4):448-457. doi: 10.4161/onci.19788. PMID: 22754763; PMCID: PMC3382881.

- Walle T, Kraske JA, Liao B, Lenoir B, Timke C, von Bohlen Und Halbach E, Tran F, Griebel P, Albrecht D, Ahmed A, Suarez-Carmona M, Jiménez-Sánchez A, Beikert T, Tietz-Dahlfuß A, Menevse AN, Schmidt G, Brom M, Pahl JHW, Antonopoulos W, Miller M, Perez RL, Bestvater F, Giese NA, Beckhove P, Rosenstiel P, Jäger D, Strobel O, Pe'er D, Halama N, Debus J, Cerwenka A, Huber PE. Radiotherapy orchestrates natural killer cell dependent antitumor immune responses through CXCL8. Sci Adv. 2022 Mar 25;8(12):eabh4050. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abh4050. Epub 2022 Mar 23. PMID: 35319989; PMCID: PMC8942354.

- Ong S, Ligons DL, Barin JG, Wu L, Talor MV, Diny N, Fontes JA, Gebremariam E, Kass DA, Rose NR, Čiháková D. Natural killer cells limit cardiac inflammation and fibrosis by halting eosinophil infiltration. Am J Pathol. 2015 Mar;185(3):847-61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.11.023. Epub 2015 Jan 23. PMID: 25622543; PMCID: PMC4348473.

- Ayach BB, Yoshimitsu M, Dawood F, Sun M, Arab S, Chen M, Higuchi K, Siatskas C, Lee P, Lim H, Zhang J, Cukerman E, Stanford WL, Medin JA, Liu PP. Stem cell factor receptor induces progenitor and natural killer cell-mediated cardiac survival and repair after myocardial infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Feb 14;103(7):2304-9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510997103. Epub 2006 Feb 7. PMID: 16467148; PMCID: PMC1413746.

- Boukouaci W, Lauden L, Siewiera J, Dam N, Hocine HR, Khaznadar Z, Tamouza R, Borlado LR, Charron D, Jabrane-Ferrat N, Al-Daccak R. Natural killer cell crosstalk with allogeneic human cardiac-derived stem/progenitor cells controls persistence. Cardiovasc Res. 2014 Nov 1;104(2):290-302. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu208. Epub 2014 Sep 11. PMID: 25213554.

- Knorr M, Münzel T, Wenzel P. Interplay of NK cells and monocytes in vascular inflammation and myocardial infarction. Front Physiol. 2014 Aug 14;5:295. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00295. PMID: 25177297; PMCID: PMC4132269.

- Ong S, Rose NR, Čiháková D. Natural killer cells in inflammatory heart disease. Clin Immunol. 2017 Feb;175:26-33. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2016.11.010. Epub 2016 Nov 25. PMID: 27894980; PMCID: PMC5315604.

- Vosshenrich CA, Di Santo JP. Developmental programming of natural killer and innate lymphoid cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013 Apr;25(2):130-8. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.02.002. Epub 2013 Mar 13. PMID: 23490162.

- Schömig K, Busch G, Steppich B, Sepp D, Kaufmann J, Stein A, Schömig A, Ott I. Interleukin-8 is associated with circulating CD133+ progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2006 May;27(9):1032-7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi761. Epub 2006 Feb 2. PMID: 16455670.

- Han ZJ, Li YB, Yang LX, Cheng HJ, Liu X, Chen H. Roles of the CXCL8-CXCR1/2 Axis in the Tumor Microenvironment and Immunotherapy. Molecules. 2021 Dec 27;27(1):137. doi: 10.3390/molecules27010137. PMID: 35011369; PMCID: PMC8746913.

- Karin M, Lin A. NF-kappaB at the crossroads of life and death. Nat Immunol. 2002 Mar;3(3):221-7. doi: 10.1038/ni0302-221. PMID: 11875461.

- Jha NK, Jha SK, Kar R, Nand P, Swati K, Goswami VK. Nuclear factor-kappa β as a therapeutic target for Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2019 Jul;150(2):113-137. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14687. Epub 2019 Mar 26. PMID: 30802950.

- Díaz-Flores L, Gutiérrez R, García MP, González-Gómez M, Díaz-Flores L Jr, Carrasco JL, Madrid JF, Rodríguez Bello A. Comparison of the Behavior of Perivascular Cells (Pericytes and CD34+ Stromal Cell/Telocytes) in Sprouting and Intussusceptive Angiogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Aug 12;23(16):9010. doi: 10.3390/ijms23169010. PMID: 36012273; PMCID: PMC9409369.

- Díaz-Flores L, Gutiérrez R, García-Suárez MP, Sáez FJ, Gutiérrez E, Valladares F, Carrasco JL, Díaz-Flores L Jr, Madrid JF. Morphofunctional basis of the different types of angiogenesis and formation of postnatal angiogenesis-related secondary structures. Histol Histopathol. 2017 Dec;32(12):1239-1279. doi: 10.14670/HH-11-923. Epub 2017 Aug 1. PMID: 28762232.

- Akbarian M, Bertassoni LE, Tayebi L. Biological aspects in controlling angiogenesis: current progress. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022 Jun 7;79(7):349. doi: 10.1007/s00018-022-04348-5. PMID: 35672585; PMCID: PMC10171722.

- Massa M, Rosti V, Ferrario M, Campanelli R, Ramajoli I, Rosso R, De Ferrari GM, Ferlini M, Goffredo L, Bertoletti A, Klersy C, Pecci A, Moratti R, Tavazzi L. Increased circulating hematopoietic and endothelial progenitor cells in the early phase of acute myocardial infarction. Blood. 2005 Jan 1;105(1):199-206. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1831. Epub 2004 Sep 2. PMID: 15345590.

- Banovic M, Poglajen G, Vrtovec B, Ristic A. Contemporary Challenges of Regenerative Therapy in Patients with Ischemic and Non-Ischemic Heart Failure. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2022 Dec 1;9(12):429. doi: 10.3390/jcdd9120429. PMID: 36547426; PMCID: PMC9783726.

- Sun Z, Wu J, Fujii H, Wu J, Li SH, Porozov S, Belleli A, Fulga V, Porat Y, Li RK. Human angiogenic cell precursors restore function in the infarcted rat heart: a comparison of cell delivery routes. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008 Jun;10(6):525-33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.04.004. Epub 2008 May 19. PMID: 18490195.

- Brodarac A, Šarić T, Oberwallner B, Mahmoodzadeh S, Neef K, Albrecht J, Burkert K, Oliverio M, Nguemo F, Choi YH, Neiss WF, Morano I, Hescheler J, Stamm C. Susceptibility of murine induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes to hypoxia and nutrient deprivation. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015 Apr 23;6(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0057-6. PMID: 25900017; PMCID: PMC4445302.

- Razeghian-Jahromi I, Matta AG, Canitrot R, Zibaeenezhad MJ, Razmkhah M, Safari A, Nader V, Roncalli J. Surfing the clinical trials of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in ischemic cardiomyopathy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021 Jun 23;12(1):361. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02443-1. PMID: 34162424; PMCID: PMC8220796.

- Hare JM, Fishman JE, Gerstenblith G, DiFede Velazquez DL, Zambrano JP, Suncion VY, Tracy M, Ghersin E, Johnston PV, Brinker JA, Breton E, Davis-Sproul J, Schulman IH, Byrnes J, Mendizabal AM, Lowery MH, Rouy D, Altman P, Wong Po Foo C, Ruiz P, Amador A, Da Silva J, McNiece IK, Heldman AW, George R, Lardo A. Comparison of allogeneic vs autologous bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells delivered by transendocardial injection in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: the POSEIDON randomized trial. JAMA. 2012 Dec 12;308(22):2369-79. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.25321. Erratum in: JAMA. 2013 Aug 21;310(7):750. George, Richard [added]; Lardo, Albert [added]. PMID: 23117550; PMCID: PMC4762261.

- Burst VR, Gillis M, Pütsch F, Herzog R, Fischer JH, Heid P, Müller-Ehmsen J, Schenk K, Fries JW, Baldamus CA, Benzing T. Poor cell survival limits the beneficial impact of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation on acute kidney injury. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2010;114(3):e107-16. doi: 10.1159/000262318. Epub 2009 Dec 2. PMID: 19955830.

- Ikebe C, Suzuki K. Mesenchymal stem cells for regenerative therapy: optimization of cell preparation protocols. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:951512. doi: 10.1155/2014/951512. Epub 2014 Jan 6. PMID: 24511552; PMCID: PMC3912818.

- Mathiasen AB, Jørgensen E, Qayyum AA, Haack-Sørensen M, Ekblond A, Kastrup J. Rationale and design of the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of intramyocardial injection of autologous bone-marrow derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in chronic ischemic Heart Failure (MSC-HF Trial). Am Heart J. 2012 Sep;164(3):285-91. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.05.026. PMID: 22980293.

- Porat Y, Porozov S, Belkin D, Shimoni D, Fisher Y, Belleli A, Czeiger D, Silverman WF, Belkin M, Battler A, Fulga V, Savion N. Isolation of an adult blood-derived progenitor cell population capable of differentiation into angiogenic, myocardial and neural lineages. Br J Haematol. 2006 Dec;135(5):703-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06344.x. PMID: 17052254.

- Rombouts WJ, Ploemacher RE. Primary murine MSC show highly efficient homing to the bone marrow but lose homing ability following culture. Leukemia. 2003 Jan;17(1):160-70. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402763. PMID: 12529674.

- Arom KV, Ruengsakulrach P, Jotisakulratana V. Intramyocardial angiogenic cell precursor injection for cardiomyopathy. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2008 Apr;16(2):143-8. doi: 10.1177/021849230801600213. PMID: 18381874.

Content Alerts

SignUp to our

Content alerts.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.