Medicine Group 2025 May 14;6(5):439-443. doi: 10.37871/jbres2101.

Multivessel Minimally Invasive Coronary Bypass with Aortic Crossclamp. Experience with 40 First Patients

Naïla El Nakadi, Sebastien D’ulisse, Karim Homsy, Serge Cappeliez, Badih El Nakadi and Sotirios Marinakis*

Abstract

Background: Minimally Invasive Coronary Revascularization (MICS-CABG) has been performed for over 20 years; however, their technical complexity, steep learning curves and absence of training programs explain the weak acceptance of these techniques. Multivessel coronary pathology consists of an extra challenge for complete revascularization in a minimally invasive setup. Cardiopulmonary bypass with cardiac cardioplegic arrest gives the possibility to a minimally invasive full coronary revascularization despite the complexity of coronary lesions.

Objectives: The aim of this article is to report on our short-term outcomes and to share our experience on multivessel MICS-CABGs with aortic crossclamp on our 40 first consecutive patients.

Methods: All patients who benefited from a scheduled multivessel MICS-CABG with aortic crossclamp in our hospital, from February 2022 to November 2023 (n = 40) were identified. Baseline demographics, peri, postoperative and laboratory data were extracted from each patient’s medical records. The 30 days results were reported.

Results: We started our minimal invasive coronary artery program on July 2018. However, difficulty addressing every coronary pathology in a minimally invasive off pump operation motivated us to adopt femorofemoral cardiopulmonary bypass and aortic crossclamp for patients with multivessel MICS-CABGs. The first 5 patients were operated on using a right thoracoscopic approach for aortic crossclamp. For the remaining 35 we adopted the TCRAT (Total Coronary Revascularization via Left Thoracotomy) technique with aortic crossclamp from the left. The average number of coronary anastomoses was 3.5 +/- 0.75, with aortic cross-clamp time 126 +/- 25min and total extracorporeal circulation (ECC) 166 +/- 36min. One Major Adverse Cardiac Event (MACE) was observed which was a death at postoperative day 9 due to pneumonia infection. Twenty-two patients were operated through the 3rd intercostal space and 18 from the fourth. Left internal mammary artery was harvested either thoracoscopically or under direct view regarding patient’s anatomy.

Conclusions: Multivessel MICS-CABG is a technically demanding operation. ECC and heart cardioplegic arrest expand MICS-CABGs indications to almost every patient.

Introduction

Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery (MICS) has undergone significant development. Valve minimally invasive surgery is the locomotive of this development with ministernotomy, minithoracotomy and endoscopic approaches gaining more and more ground in the management of these pathologies. Minithoracotomy approaches for coronary surgery represent an important technical complexity making the adoption of these procedures more difficult.

Minithoracotomy coronary surgery appeared in the middle 90s, the well-known Minimally Invasive Direct Coronary Artery Bypass (MIDCAB) [1]. This operation is performed through a left minithoracotomy. The surgeon harvests the Left Internal Mammary Artery (LIMA) through direct view and performs a LIMA to Left Anterior Descending Artery (LAD) bypass without cardiopulmonary bypass.

Only a few cardiac centers worldwide offer multivessel minimally invasive beating-heart coronary bypass procedures, an operation known with the acronym MICS-CABGs (Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery- Coronary Artery Bypass Graft). This operation is characterized by a considerable technical complexity with very few cardiac surgeons performing it worldwide. Moreover, it is rarely performed on an all-comers basis, and careful patient selection is usually required [2].

To bring this operation to more patients (practically with no patient selection) MICS-CABGs can be facilitated with the use of extracorporeal circulation and aortic cross-clamp [3]. Moreover, according to surgeon’s experience graft harvesting of IMAs can be performed endoscopically which decreases surgical access invasiveness [4-8].

The aim of this series is to report the short-term outcome of our series of the first 40 consecutive patients who benefited from a multivessel MICS-CABG operated on pump with aortic cross clamp through a left minithoracotomy.

Case Series

This retrospective study was carried out in our Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, in CHU Charleroi Marie Curie Hospital. All patients who benefited from an on-pump MICS-CABG between February 2022 to November 2023 (n = 40) were identified. Baseline demographics, perioperative data, postoperative outcomes and laboratory data were prospectively recorded. Patients were followed up for a minimum of 30 days. They were operated by one surgeon and represent all his and his team’s experience on the technique. However, the principal surgeon had performed more than a hundred minimally invasive beating heart coronary bypass surgeries, either with single vessel or multivessel disease, being already familiar with minimal access coronary surgery.

Results were reported according to the intent-to-treat principle. Continuous variables were reported as median and interquartile range and nominal as frequency and percentage values.

Operation

Preoperative evaluation before on pump MICS-CABGs is the same as standard coronary surgery with the addition of a thoracoabdominal Computed Tomography Scan (CT Scan). The aim of this exam is to evaluate if peripheral femoral cannulation is feasible and to exclude ascending aorta atheromatosis which would be an absolute contra-indication for aortic cross-clamp.

The anesthesiologic setup does not differ either from standard coronary surgery with the exception that if a direct view LIMA harvesting is to be performed a double lumen endotracheal tube should be used to exclude left lung during harvesting. If we opt for an endoscopic LIMA harvesting no lung exclusion is needed because harvesting is performed under CO2 inflation which opens the space between the lung and the anterior hemithorax. Moreover, a perioperative transesophageal echocardiogram is needed for guiding peripheral femoral cannulation.

The patient is placed in a decubitus position with a 3-liter pressure pocket placed below his left hemithorax. The pocket is inflated to slightly elevate the left hemithorax which opens intercostal spaces. For lateral targets our second conduit choice is the left radial artery which was harvested before LIMA.

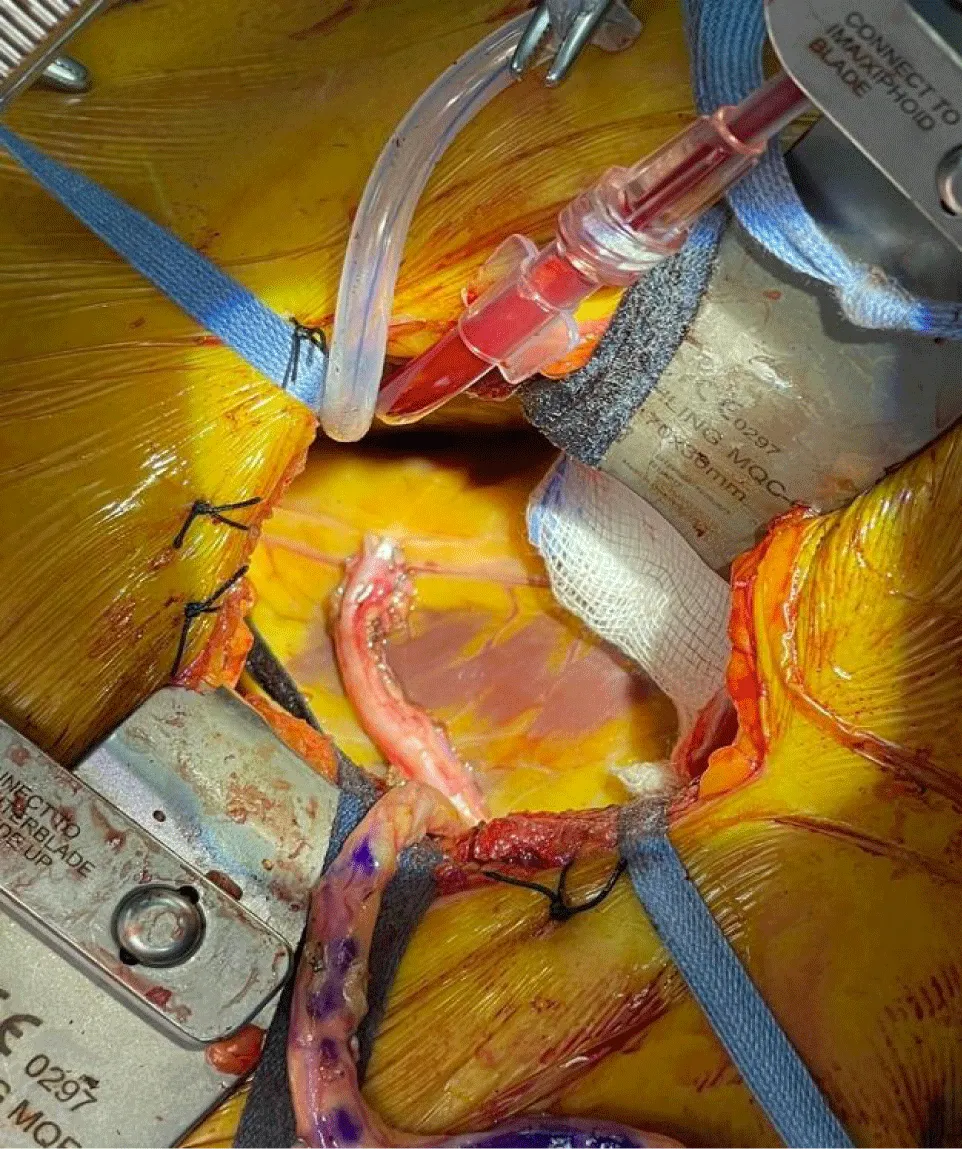

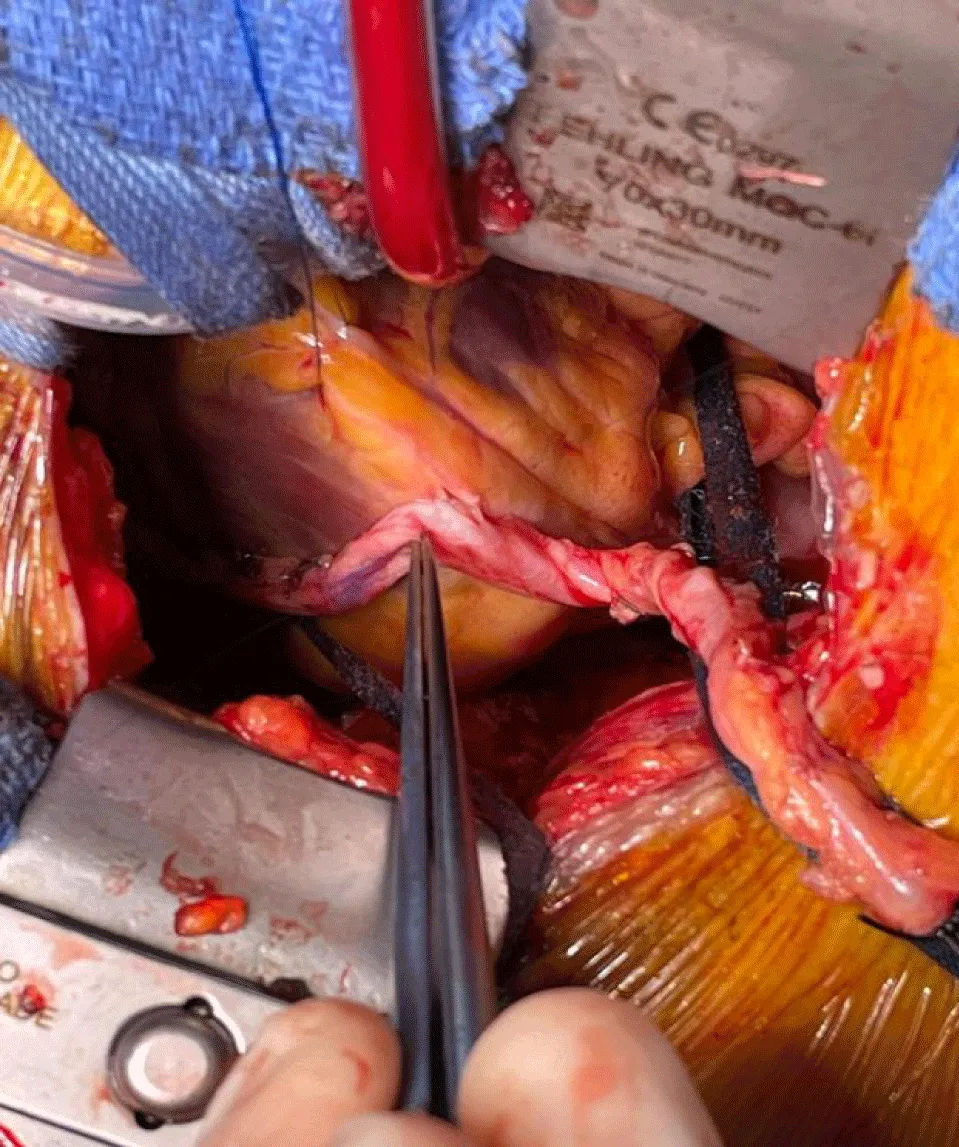

The operation starts with the thoracoscopic LIMA harvesting through two 5mm trocars working trocars and one 10mm camera port (Figure 1). After the administration of 10000U of heparin, LIMA is divided and pericardium opened. Target vessels are evaluated and the thoracic incision is realized at the level needed (usually at the 4th intercostal space) from where all target coronary vessels can be reached with the adequate maneuvers (Figures 2,3). A special retractor (Fehling retractor) which can elevate the left hemithorax was used after the fifth patient to give better access to the ascending aorta for cross-clamp preparation. When LIMA is harvested under direct view through the minithoracotomy the Fehling retractor is used. Our preferred grafts are the LIMA for LIMA to LAD anastomosis and the left radial artery for the other target coronary lesions in a T graft configuration (Figures 2,3).

Results- Discussion

Patients’ demographics, perioperative data and complications are summarized in tables 1,2. Our patients had a median Euroscore II of 1.2%, a median age of 65.7 years and a BMI of 27.1. Half our patients where diabetics, 75% were operated electively and 67.5% had a good left ventricular function.

| Table 1: Multivessel MICS-CABG with aortic crossclamp (n = 40) Demographic Data. | |||

| Age in years. median (IQR) | 65.7 (58.9 - 70.4) | Hypercholesterolemia | 35 / 40 (87.5) |

| BMI. median (IQR) | 27.1 (25.2 - 31.7) | Preoperative AF. n (%) | 0 |

| Male Gender. n (%) | 34 / 40 (85) | Chronic Lung Disease. n (%) | 1 / 40 (2.5) |

| Euroscore II. median (IQR) | 1.2 (0.9 - 1.8) | Cerebrovascular accident. n | 3 / 40 (7.5) |

| Creatinine clearance. median (IQR) (ml / min) | 71.4 (62.6 - 93.4) | Recent myocardial infarction. n (%) | 7 / 40 (17.5) |

| Dialysis. n (%) | 1 / 40 (2.5) | Elective surgery. n (%) | 30 / 40 (75) |

| Diabetes. n (%) | 19 / 40 (52.5) | NYHA III or IV. n (%) | 7 /40 (7.5) |

| Tobacco history. n (%) | 22 / 40 (55) | Good LVEF (> 50%). n (%) | 27 / 40 (67.5) |

| Hypertension. n (%) | 29 / 40 (72.5) | Reoperation. n (%) | 0 |

| Table 2: Multivessel MICS-CABG with aortic crossclamp (n = 40) Peri and Post-operative Data. | |||

| Number of distal anastomoses. median (IQR) (min) | 3 (3-4) | Need for transfusion. n (%) | 18 / 40 (45) |

| Hybrid Revascularization. n (%) | 1 / 40 (2.5) | New onset postoperative AF. n (%) | 7 / 40 (17.5) |

| Conversion to sternotomy. n (%) | 0 | Reoperation for bleeding. n (%) | 1 / 40 (2.5) |

| ECC duration. median (IQR) (min) | 164.5 (145.5 - 191.5) | Target vessel revascularization in hospital. n (%) | 0 |

| Cross Clamp Time. median (IQR) (min) | 121.5 (103.8 - 143) | Postoperative intubation time. median (IQR) (hours) | 9 (6 - 16) |

| Postoperative length of stay. median (IQR) (days) | 8 (7 - 9) | Myocardial Infarction in hospital. n (%) | 0 |

| Intensive Care Unit length of stay. median (IQR) (hours) | 65.5 (41.3 - 89) | Mortality in hospital. n | 1 / 40 (2.5) |

| Stroke. in hospital | 1 / 40 (2.5) | MACE in hospital. n (%) | 2 / 40 (5) |

| Drain output at 24 h. median (IQR) (ml) | 610 (400 - 932.5) | ||

The use of cardiopulmonary bypass permitted us a high number of peripheral anastomosis per patient (mean number of anastomoses: 3.5 +/- 0.75). The median time of cardiopulmonary bypass and aortic cross-clamp was 164.5 and 121.5 minutes respectively. Patients had a median stay of 2.5 days in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and 8 days of median postoperative length of stay.

In our series we had one revision for bleeding, one postoperative stroke and one death due to nosocomial pneumonia at postoperative day 9. We observed no target vessel revascularizations and no postoperative infarctions. As a result, the number of major adverse cardiovascular events observed (MACE) was 2/40 (5%).

Minimal invasive CABG with the use extracorporeal circulation and aortic cross-clamp increases the indications of MICS-CABGs to almost every patient. Absolute contraindications for this technique are a calcified ascending aorta making it dangerous to perform an aortic cross-clamp and no vessel access for safe peripheral vascular cannulation.

Although this series represents our initial experience with the technique, no increase mortality or morbidity were observed in comparison to a standard approach through median sternotomy [9]. Sternal sparing cardiac operations minimize to zero all complications of sternal healing and sternal infections which although are rare represent a major morbidity and mortality aspect of CABG through median sternotomy [10]. Moreover, minimizing invasiveness in surgery enhances patients’ satisfaction and demonstrates respect to the physical and mental integrity of the patient.

Long term results are a prerequisite to prove that this technique can be safely proposed to every patient who needs a CABG operation. However, our short-term results are very promising. Our patients demonstrated an important satisfaction after this operation, with no increase in perioperative and short-term postoperative morbidity regarding patients who are benefiting of a classic full sternotomy approach, although we were in our initial period of learning curve.

We believe that this technique can become the standard of care for patients in need of a CABG operation. The use of aortic cross-clamp facilitates increasing inclusion criteria for MICS-CABG to almost all patients. However, it is a more demanding operation than full sternotomy CABG and probably, our good results in our initial phase of implication of the technique are in part due to our extensive experience on beating heart MICS-CABGs.

References

- Benetti FJ, Ballester C. Use of thoracoscopy and a minimal thoracotomy, in mammary-coronary bypass to left anterior descending artery, without extracorporeal circulation. Experience in 2 cases. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 1995 Apr;36(2):159-61. PMID: 7790335.

- McGinn JT Jr, Usman S, Lapierre H, Pothula VR, Mesana TG, Ruel M. Minimally invasive coronary artery bypass grafting: dual-center experience in 450 consecutive patients. Circulation. 2009 Sep 15;120(11 Suppl):S78-84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.840041. PMID: 19752390.

- Babliak O, Demianenko V, Melnyk Y, Revenko K, Pidgayna L, Stohov O. Complete Coronary Revascularization via Left Anterior Thoracotomy. Innovations (Phila). 2019 Aug;14(4):330-341. doi: 10.1177/1556984519849126. Epub 2019 May 20. PMID: 31106625.

- Oehlinger A, Bonaros N, Schachner T, Ruetzler E, Friedrich G, Laufer G, Bonatti J. Robotic endoscopic left internal mammary artery harvesting: what have we learned after 100 cases? Ann Thorac Surg. 2007 Mar;83(3):1030-4. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.055. PMID: 17307454.

- Marinakis S, Homsy K, Nakadi BE. Evolution of Surgical Expertise in Endoscopic Assisted Minimally Invasive Coronary Artery Bypass: Experience With 70 Consecutive Patients. Innovations (Phila). 2024 Mar-Apr;19(2):207-209. doi: 10.1177/15569845241237482. Epub 2024 Apr 4. PMID: 38576097.

- Marinakis S, Chaskis E, Cappeliez S, Homsy K, De Bruyne Y, Dangotte S, Poncelet A, Lelubre C, El Nakadi B. Minimal invasive coronary surgery is not associated with increased mortality or morbidity during the period of learning curve. Acta Chir Belg. 2023 Oct;123(5):481-488. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2022.2076971. Epub 2022 May 20. PMID: 35546309.

- Marinakis S, Lalmand J, Cappeliez S, De Bruyne Y, Viste C, Aminian A, Dolatabadi D, El Nakadi B. An asymptomatic Lima dissection after a programmed hybrid revascularization procedure turned to nightmare. Acta Chir Belg. 2022 Oct;122(5):370-372. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2020.1871289. Epub 2021 Jan 21. PMID: 33399525.

- Yilmaz A, Robic B, Starinieri P, Polus F, Stinkens R, Stessel B. A new viewpoint on endoscopic CABG: technique description and clinical experience. J Cardiol. 2020 Jun;75(6):614-620. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2019.11.007. Epub 2020 Jan 8. PMID: 31926795.

- Sandner S, Misfeld M, Caliskan E, Böning A, Aramendi J, Salzberg SP, Choi YH, Perrault LP, Tekin I, Cuerpo GP, Lopez-Menendez J, Weltert LP, Böhm J, Krane M, González-Santos JM, Tellez JC, Holubec T, Ferrari E, Doros G, Vitarello CJ, Emmert MY; Registry Investigators; European DuraGraft Registry investigators’. Clinical outcomes and quality of life after contemporary isolated coronary bypass grafting: a prospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2023 Apr 1;109(4):707-715. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000259. PMID: 36912566; PMCID: PMC10389413.

- Singh K, Anderson E, Harper JG. Overview and management of sternal wound infection. Semin Plast Surg. 2011 Feb;25(1):25-33. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275168. PMID: 22294940; PMCID: PMC3140234.

Content Alerts

SignUp to our

Content alerts.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.