Medicine Group 2025 May 17;6(5):465-491. doi: 10.37871/jbres2104.

The Role of Translation Initiation Regulation in Tumorigenesis, Progression and Drug Resistance

Shi-Lin Lin1,2†, Yue Wang1,2†, Jia Fan1,2, Chao Gao1,2* and Ai-Wu Ke1,2*

2Key Laboratory of Carcinogenesis and Cancer Invasion, Department of Liver Surgery, Ministry of Education, Zhongshan Hospital, Liver Cancer Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai, China

†These authors shared co-first authorship

- Translation initiation

- Cancer

- Drug resistance

Abstract

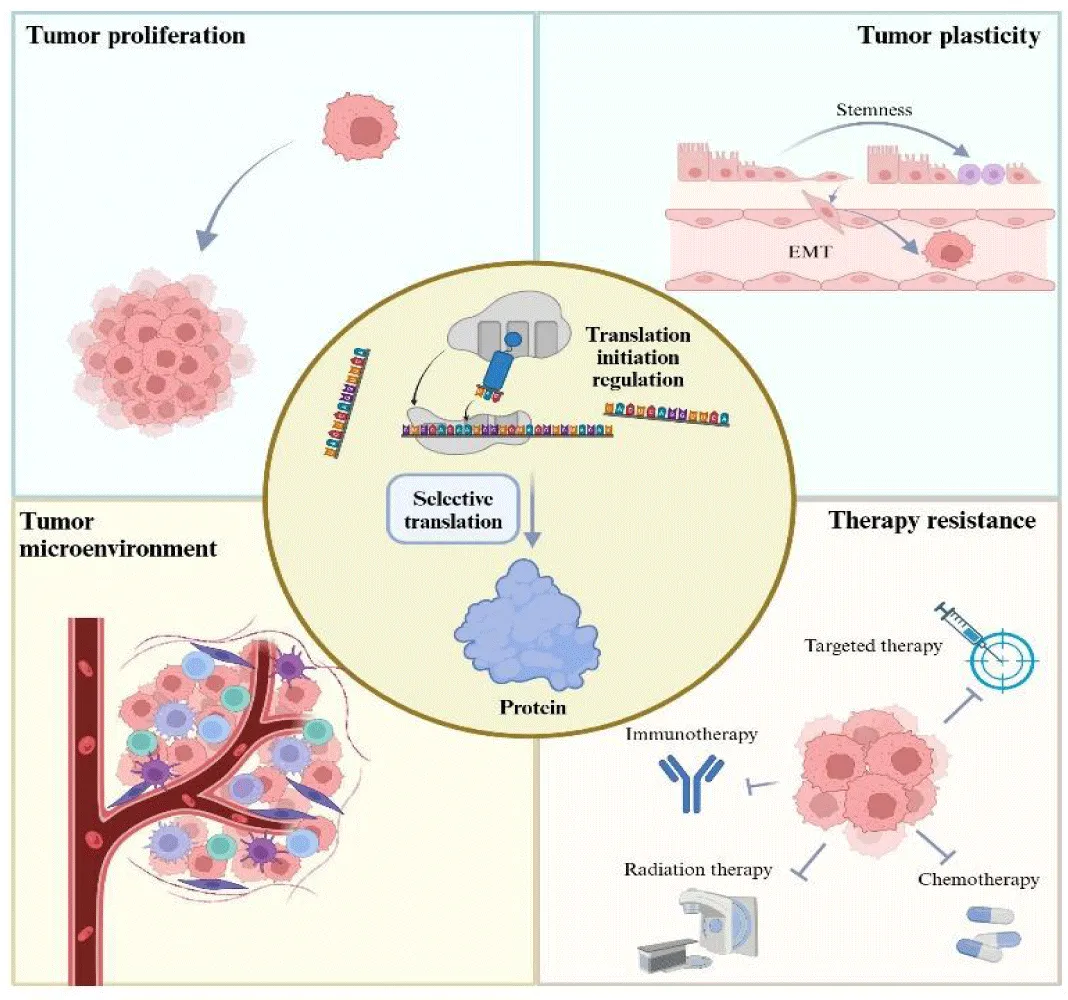

The initiation of mRNA translation plays a pivotal role in gene expression and has profound implications for tumorigenesis, tumor progression, and drug resistance. eIF4F complex, as an important part of the classical translation initiation mechanism, has been widely studied in tumors, and tumor cells use it to enhance overall protein synthesis while while targeting the translation of oncogenes. In addition, the roles of a number of other translation initiation factors and translation initiation-related pathways (such as mTOR) in tumorigenesis and development have also been gradually discovered. Previous reports have shown that dysregulated translation initiation could enable tumor cells to thrive in challenging environments, such as hypoxia. These intricate processes are essential for adapting to complex circumstances and transforming the tumor immune microenvironment. This transformation equips cancer cells with the ability to evade detection by the immune system. Moreover, the dysfunction of translation initiation may cause drug resistance among tumors. This disruption increases the production of specific proteins that act as essential support systems for cancer cells, which enables them to withstand the adverse effects of various cancer treatments and increases the challenges in combating the disease. In this review, we examine the significance of translation initiation regulation in tumorigenesis and cancer development and highlight how abnormalities in translation initiation can cause drug resistance in tumors. We also evaluate the feasibility of developing combination therapies that target translation initiation in conjunction with other anticancer agents.

Introduction

Gene expression refers to a fundamental biological process that includes two primary steps: transcription and translation. Typically, the functional expression of genes is regulated through these sequential processes, ensuring precise control over genetic activity. However, for many cellular genes, there are considerable variations in the levels of mRNAs and their corresponding proteins. This variation is attributed to the splicing mechanisms involved in the maturation of mRNAs as well as the regulatory processes governing mRNA translation [1].

The translation of mRNA plays a vital role in converting the genetic code encoded in mRNA into functional proteins, which are essential for the survival and adaptability of cells. This process consists of four main stages: initiation, elongation, termination, and ribosome recycling. Among these stages, initiation, as a key step in protein synthesis, is always subject to various regulatory mechanisms [2]. The effective regulation of translation initiation is essential for maintaining the optimal level of intracellular protein synthesis and ensuring the production of specific proteins across diverse environments. Disruption of this regulatory mechanism can result in severe impairments in protein expression, functionality, and overall cellular homeostasis, which play critical roles in the development and progression of various diseases [3].

Tumor cells are distinguished by elevated levels of protein synthesis. Additionally, these cells are able to produce specific proteins in response to changes in their surrounding microenvironment, which help them adapt and thrive under varying conditions. In this context, the regulation of translation initiation plays a significant role in tumor development [4]. The abnormal expression and activation of Eukaryotic Initiation Factors (EIFs) in various tumors correlates with poor prognoses. These irregularities in the process of translation initiation lead to the misregulation of essential oncogenes that drive the onset and progression of cancer and also to the promotion of aggressive proliferation and invasive migration of cancer cells. Moreover, cancer cells frequently face harsh challenges within their microenvironment, including hypoxia, a deficiency of crucial nutrients, and evasion of immune response cells. In these adverse situations, the dysregulation of translation initiation becomes even more pronounced, ultimately shaping an environment that promotes tumor growth and survival [5].

The Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (MTOR) and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways participate in various cellular processes, influencing how cells respond to their environment and communicate with one another. These pathways also play significant roles in the translational reprogramming of tumors, enabling cancer cells to modify protein synthesis to support their uncontrolled growth and proliferation. When these pathways become abnormally activated, they can cause profound changes in protein expression levels, leading to detrimental effects on normal cellular functions and contributing to cancer progression.

EIFs, especially eIF4E, are key players in this dysfunction. The eIF4E protein is critical for initiating the translation of specific mRNAs that drive tumor cell survival, growth, and transformation, allowing cancer cells to evade normal regulatory mechanisms and thrive despite unfavorable conditions [6]. The process of translation initiation is also closely associated with the development of resistance to a wide range of cancer therapies [7]. Research has shown that implementing targeted interventions during translation initiation can significantly enhance the sensitivity of cancer cells to these therapies, improving patient outcomes [8]. However, a comprehensive characterization of the relationships between translation initiation regulation and tumor dynamics is needed to fully understand the complex biological processes involved in cancer development. A better understanding of these processes may lead to the identification of innovative targets for anti-tumor therapies.

In this review, we describe recent advancements in research focused on the regulation of translation initiation, particularly in relation to drug resistance observed in tumors. By understanding how translation initiation influences tumor survival and adaptation, we can gain insights into the mechanisms that cancer cells use to resist treatment. We also discuss the potential advantages of combining various therapeutic agents, which is a strategy aimed at enhancing the overall effectiveness of cancer treatments, especially those resistant cancer types that pose significant challenges in clinical settings.

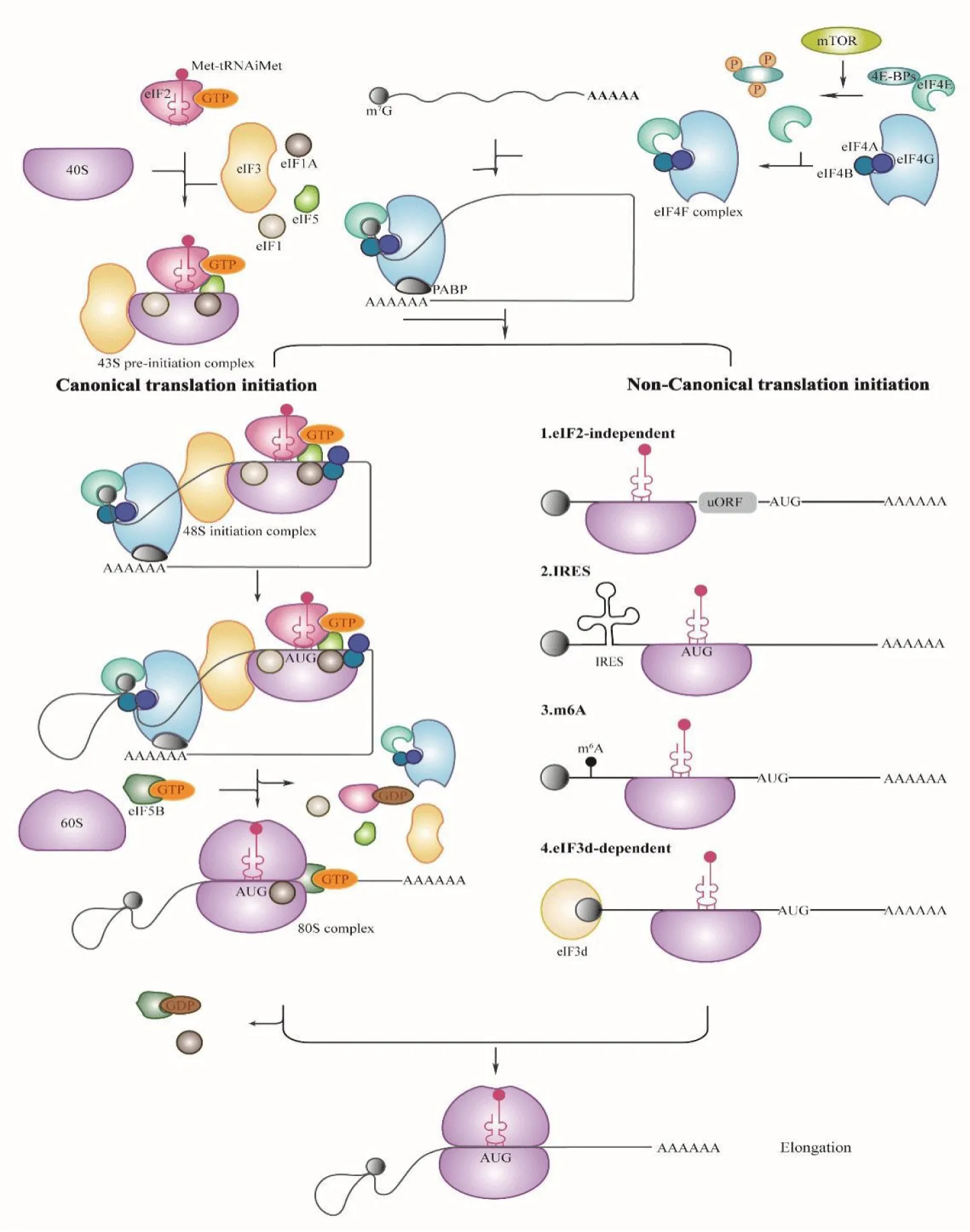

The mRNA Translation Initiation Process

The initiation of mRNA translation is a highly intricate process that requires precise interactions between several key components, including ribosomes, methionine initiator transfer RNA, and various eIFs. In this classical mode of translation, often referred to as cap-dependent translation, the initiation complex assembles at the 5' cap of the mRNA molecule (Figure 1). The initiation of protein synthesis begins with creation of the 43S pre-initiation complex, which consists of eIF1, eIF1A, eIF3, and eIF5, alongside a Ternary Complex (TC) that brings together eIF2, Guanosine 5'-Triphosphate (GTP), and methionine initiator transfer RNA. In addition, the small ribosomal subunit, known as 40S, is recruited to the assembly [9].

Complementing this process is the eIF4F complex, which plays a vital role in mRNA recognition and binding. The eIF4F complex consists of three main proteins: eIF4E, which is responsible for recognizing and binding the 5' cap of the mRNA; eIF4G, a scaffolding protein that facilitates the assembly of other eIFs; and eIF4A, an RNA helicase that unwinds secondary structures in the mRNA. eIF4F binds to the mRNA, recruiting the 43S ribosomal subunit and forming the 48S initiation complex, which is a key step in translation that is supported by the eIF3 protein [10]. eIF3 is a protein complex comprised of 13 subunits that regulate the attachment of essential components to mRNA and accurately identify start sites for protein synthesis [11]. The Poly(A)-Binding Protein (PABP) engages in mRNA translation initiation by establishing a connection between eIF4G and the poly(A) tails found at the 3ʹ end of the mRNA molecule. This interaction results in the formation of a closed-loop structure consisting of the cap, eIF4E, eIF4G, PABP, and the poly(A) sequence. This closed-loop model significantly enhances the binding affinity of eIF4E to the cap, promoting the reactivation of translation [12].

Recognition of the AUG initiation codon involves a complex interaction within the scanning 5ʹ Untranslated Region (UTR) of the 48S initiation complex. This process relies on the precise identification of the codon by eIF1 and eIF1A. Additionally, unwinding of the RNA structure is facilitated by the action of eIF4A along with its cofactor eIF4B [13]. Upon recognition of the AUG initiation codon by the 48S initiation complex, the eIF2 molecule binds to GTP, and the GTP undergoes hydrolysis. This reaction triggers a series of changes, resulting in the release of eIF1, eIF2, and eIF3 from the complex. Simultaneously, the 60S ribosomal subunit detaches from eIF6 [14]. This detachment allows it to interact with the 40S ribosomal subunit, which is an essential step in forming a functional complex facilitated by the GTPase eIF5B [15]. Once the 80S ribosomal complex is successfully assembled, eIF5B and eIF1A are released from the complex. This release marks a pivotal transition in the process of protein synthesis, as the machinery then advances to the elongation phase [16].

When external stimuli inhibit the traditional translation initiation process, cells can translate certain mRNAs through non-classical translation initiation mechanisms. These alternative pathways can bypass the protective cap structures, the poly(A) tails, or the standard AUG start codons that are typically required for classical translation initiation, including pathways such as the Internal Ribosomal Entry Site (IRES), mRNA adenosine N6 methylation (m6A), and eIF3d [17-19] (Figure 1). These non-classical translation initiation mechanisms are important for protein expression under certain conditions because they enable protein synthesis in response to different cellular needs. Knowledge of these non-classical translation initiation mechanisms may create new research opportunities and potential medical applications.

Regulation of Translation Initiation in Tumors

Abnormalities in the initiation of translation have been widely documented in the context of tumor development. These abnormalities influence the overall levels of cellular protein synthesis and also regulate specific proteins to address the specific needs of tumor progression. Furthermore, tumors can leverage the translation initiation mechanisms linked to the stress response to selectively produce proteins, thereby adapting to their environment and ensuring their survival. By further exploring these mechanisms, it may be possible to better understand the complicated regulatory networks that drive tumorigenesis, which in turn could identify promising targets for the development of groundbreaking therapeutic strategies for cancer. Overall, this exploration has the potential to significantly advance cancer treatment and improve patient outcomes.

Regulation of eIFs

eIFs are essential components of protein synthesis, and any modifications in these factors can significantly influence tumor development and prognosis. Identifying these changes may facilitate the advancement of cancer research and significantly improve patient outcomes [20]. Currently, a variety of novel anti-tumor pharmaceuticals targeting translation eIFs have been developed and introduced into clinical practice. These advancements provide new directions for the treatment of tumors, potentially enriching therapeutic strategies and improving patient outcomes in oncology [21].

eIF4F is a fundamental regulator in the initiation of protein translation, and it plays a critical role in the aberrant production of tumor-associated proteins. Within this complex, eIF4E is of particular importance because its overexpression serves as a major driver of enhanced protein synthesis in a variety of tumors, including breast cancer, prostate cancer, and non-small cell lung cancer [22]. Moreover, eIF4E selectively facilitates the translation of essential mRNAs that are associated with malignancy, such as c-myc, which drives cell proliferation, and B-cell lymphoma 2, which promotes the tumor resistance to apoptosis. This targeted translation process directly supports tumor growth and progression, identifying eIF4E as an important target for therapeutic intervention [23]. Studies have revealed that the eIF4E protein is typically present in greater quantities than necessary in normal cells. Tumor cells exploit this abundance of eIF4E to enhance their growth and survival by selectively promoting the translation of specific mRNAs. These mRNAs possess special sequences in their 5ʹ-UTR, which allows tumor cells to prioritize the production of proteins that support their unchecked proliferation and resistance to cell death [24]. In addition, the effects of elevated eIF4E levels on normal cells are still not fully understood. It is essential to identify the specific mechanisms through which tumors leverage abundant eIF4E to foster their growth and survival.

Previous research has also demonstrated that tumors exhibit both elevated expression levels and enhanced activity of eIF4E, potentially contributing to their malignant characteristics. This enhanced activity is regulated by the mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways, both of which play key roles in cellular processes such as growth, metabolism, and proliferation [25,26]. The Phosphatidylinositol 3ʹ-Kinase (PI3K)-Protein Kinase B (AKT)-mTOR pathway is vital for regulating cellular processes, primarily through the phosphorylation of eIF4E-Binding Proteins (4E-BPs). This process results in the release of eIF4E from these proteins, allowing eIF4E to bind with eIF4G to form the eIF4F complex, which is essential for initiating protein synthesis [27].

In tumors, cells have been shown to strategically manipulate the mTOR signaling pathway to control protein synthesis, promoting their growth and proliferation. By facilitating the interaction between eIF4E and eIF4G, the mTOR pathway enhances protein production in tumor cells, contributing to their survival and aggressiveness [28,29]. MAP Kinase-Interacting Kinases 1(MNK1) and MNK2 are integral to the regulation of translation activity through the phosphorylation of eIF4E Robichaud N, et al. [30]. Demonstrated that the inhibition of eIF4E phosphorylation results in a reduction in the metastatic potential of breast cancer cells, specifically in their ability to disseminate to the lungs [30]. As a critical scaffolding protein within the eIF4F complex, eIF4G overexpression is also associated with tumor progression. This protein engages in a cap-binding mechanism and also uses IRES to enhance the process of protein translation [31,32].

The deconjugation activity of eIF4A is also regulated by the mechanistic target of mTOR, which affects the deconjugation process by phosphorylating ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) through two significant mechanisms that are vital for cellular function. First, mTOR phosphorylates the tumor suppressor protein known as programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4), which is important for regulating cellular apoptosis and growth. This phosphorylation event modulates the stability and activity of PDCD4, thus impacting the overall cellular environment [33]. Second, mTOR phosphorylates the cofactor eIF4B, which enhances the dehydrogenase activity of eIF4A [34]. In the specific context of colorectal cancer, Din FVN, et al. [35] showed that the anti-inflammatory drug aspirin exerts its effects by inhibiting the mTOR pathway. This inhibition leads to a decrease in the phosphorylation of both S6K1 and 4E-BP1, two proteins that are integral to the regulation of protein synthesis and tumor growth, which suppresses tumor growth. Research has also shown that the expression levels of eIF4A, along with its cofactors eIF4B and eIF4H, are significantly elevated in a variety of tumor types [36,37].

In addition to the irregular regulation of the eIF4F complex, numerous abnormalities in other eIFs have been identified within tumor cells. The scanning and expression of most oncogenic mRNAs, which are vital for cell proliferation and the regulation of the cell cycle, significantly rely on eIF1A and eIF1. Importantly, mutations that result in the dysregulation of eIF1 have been linked to poorer prognoses in patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC), highlighting the essential role these factors play in the progression of cancer [38]. eIF2 serves as a vital component of TCs, which are essential for the initiation of protein synthesis in cells. A key subunit of eIF2, eIF2α, is mainly regulated through phosphorylation. This process is intricately connected to the GTP/ Guanosine Diphosphate (GDP) cycle, which involves the conversion of GTP into GDP. This cycle modulates the activity of eIF2 and also affects complex mechanisms involving protein production within the cell [39]. Mutations in eIF2α can lead to unregulated translation initiation, resulting in increased levels of TCs and the development of malignant tumors [40,41].

eIF3 is a critical complex that consists of 13 subunits, each serving different functions in the initiation of translation [10]. Dysregulation of these subunits has been strongly associated with a wide range of cancer types. In tumor tissues, expressions of most eIF3 subunits are upregulated, although eIF3e and eIF3F are typically downregulated. This increase in subunit expression levels significantly promotes cell proliferation, accelerates cell cycle progression, and drives metastasis through the activation of various signaling pathways [42]. The interaction between eIF5 and the eIF5 mimetic protein 1 (5MP1) is also crucial for regulating translation initiation. 5MP1 increases the abundance of TCs by competing with eIF5, preventing eIF5 from repressing the reactivation of eIF2 [43]. This competitive interaction is especially important in colorectal cancer, in which 5MP1 reprograms the expression of the c-myc gene, driving cell cycle progression and tumor growth [44]. Furthermore, eIF6 plays a crucial role in the formation of the 80S ribosomal complex. Compelling research findings indicate that increased eIF6 expression occurs in numerous tumors, driving tumor growth and migration [45,46].

In-depth study of the mechanisms of action of these factors in tumors should lead to identification of novel molecular therapeutic targets. Such targets will expand the options available for innovative and effective cancer treatment strategies and pave the way for better patient outcomes.

Regulation of ribosome heterogeneity

Ribosome abnormalities are vital for the translation initiation process and may contribute to cancer development. Oncogenes such as MYC and Ncl promote ribosome biosynthesis and protein synthesis by enhancing the transcription of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) [47]. Furthermore, heterogeneity in the two primary components of ribosomes, ribosomal proteins (RPs) and rRNA, can affect translation initiation, leading to selective translation of specific mRNAs and contributing to aberrant cellular behaviors observed in tumor cells [48]. Among these variations, 2ʹ-O-methylation (2ʹ-O-Me), pseudouridylation, and N6-methylation are the most extensively studied modifications in the context of translation [49].

2ʹ-O-Me is mediated by small nucleolar RNA [50], which alters specific sites on rRNAs and shifts the traditional patterns of translation initiation, leading to the selective production of specific proteins in cells by utilizing IRES [51]. Zeste Enhancer Homolog 2 (EZH2), an oncogene associated with colorectal cancer [52], uses these modification mechanisms to enhance the translation of specific IRES-dependent genes, driving aggressive tumor growth and survival [53]. The methyltransferase 5, N6-adenosine (METTL5) enzyme participates in this regulatory network by mediating N6-methylation of rRNA at the m6A site. This specific modification has been found to higher in various cancer cells than in healthy cells s and correlates with poor prognoses of patients [51,54]. By enhancing translation initiation, METTL5 facilitates the assembly of 80’s ribosomes, increasing overall protein synthesis and driving cancer progression [55,56].

Mutations in RPs components are also common in various tumors, highlighting their significant role in cancer biology. Certain mutations affect translation initiation. For example, Kampen, et al. [57] found that translation of the anti-apoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma 2 via the IRES is upregulated in leukemia cells harboring ribosomal protein L10 mutations. They found that this mechanism enhances protein synthesis, allowing these mutant leukemia cells to defend themselves more effectively against elevated levels of oxidative stress. As a result, this adaptation promotes cancer cell survival and leads to the persistence of cancer in the body.

Ribosomal heterogeneity plays a significant role in tumorigenesis and disease progression. Gao and Wang demonstrated that ribosomes exhibit considerable diversity across different tissues [58], and this characteristic likely will facilitate the development of therapeutic interventions targeting ribosomal heterogeneity, advancing the field of precision medicine.

Regulation of cellular stress responses

The hypoxic and nutrient-deprived environment of tumors often triggers activation of the Integrated Stress Response (ISR) in cells. This adaptive response enhances cell survival under adverse conditions [59,60]. A fundamental regulatory mechanism within the ISR is the phosphorylation of eIF2α. This phosphorylation is essential for decreasing the overall concentrations of TCs within the cell, thus limiting general protein synthesis. The ISR also facilitates selective protein translation through alternative mechanisms that circumvent traditional pathways. These mechanisms include the use of upstream open reading frames, IRES and eIF3d, which regulate the translation of downstream coding sequences. Tumors exploit these mechanisms to effectively synthesize proteins essential for their growth and development, even under inhospitable microenvironmental conditions [60]. However, the extent to which tumors exploit these mechanisms to enhance their growth under challenging conditions is not fully understood.

Transcription Factor 4 (ATF4) serves as a key effector of the ISR in cellular biology. This process begins with the phosphorylation of eIF2α, which leads to translational repression of the upstream open reading frame of ATF4 mRNA. As a result, this repression facilitates the translation of the main open reading frame, promoting the synthesis of the ATF4 protein [61]. m6A methylation of ATF4 mRNA further enhances its translation, resulting in elevated levels of ATF4 within cells [62]. The overexpression of ATF4 is frequently observed in various malignancies, where it affects several critical processes such as tumor proliferation, metastasis, and the emergence of resistance to therapeutic interventions Tameire F, et al. [63,64] identified a feed-forward interaction between the proto-oncogene Myc and ATF4, which plays a vital role in the growth and progression of Myc-dependent tumors. Leppek K, et al. [65] found that under conditions of cellular stress, Myc can initiate translation via IRES and Wiegering A, et al. [66] suggested that targeting this initiation of translation may decrease Myc expression and inhibit tumor growth. However, ATF4 can also moderate oncogenesis. For example, He F, et al. [67] reported that ATF4 appears to mitigate the progression from non-alcoholic hepatitis to HCC by inhibiting a specific form of cell death known as iron death or ferroptosis.

The dual functionality of ATF4, promoting cancer progression in certain scenarios while serving a protective role in others, likely reflects distinct stages of tumorigenesis and the specific tissue environments involved. Further in-depth investigations are essential to elucidate the mechanisms that underlie the opposing roles of ATF4. Such research has the potential to yield valuable insights for the precise targeting of ATF4, which would facilitate the development of effective strategies to inhibit tumor progression effectively and improve therapeutic outcomes for patients.

Tumors strategically utilize translation initiation mechanisms during stressful periods to synthesize crucial proteins that facilitate their adaptation to unfavorable environments. This capacity promotes their survival and establishes an environment conducive to continued growth and malignant transformation.

Regulation of Translation Initiation for Tumor Plasticity

Tumor plasticity is defined as the capacity of tumor cells to reprogram and adapt their characteristics in response to both internal signals and external environmental changes [68]. This adaptability enhances the invasive potential of cancer cells, facilitating their infiltration into surrounding tissues and promoting metastasis to distant sites. Tumor plasticity also bolsters the self-renewal capabilities of cells, which are essential for sustained tumor growth. As such, tumor plasticity serves as a critical factor driving cancer progression [69]. Recent research has emphasized the role of translation initiation in regulating cellular plasticity [69]. Examining the relationships between translation initiation and tumor plasticity should help elucidate the mechanisms that lead to the heightened malignancy of tumors. Knowledge of these mechanisms is essential for developing more effective therapeutic strategies, with the ultimate goal of improving treatment options for cancer patients.

The Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT)

The EMT is a reversible trans differentiation process that is frequently aberrantly activated in tumors. This activation is associated with various malignancies, including tumor invasion, metastasis, cellular dedifferentiation, and resistance to therapeutic interventions. The activation of the EMT is predominantly controlled by EMT transcription factors (EMT-TFs) such as Twist, Snail, and Zeb. The EMT also involves the activation of several key signaling pathways, including the transforming growth factor beta, Wnt, Notch, and Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF) pathways, all of which contribute to the complex regulatory mechanisms governing this transition [70]. Evdokimova V, et al. [71] recently showed the significant influence of translation initiation on the expression of EMT-TFs within tumors, which facilitated the induction of the EMT and its associated malignant characteristics.

The MNK and mTOR signaling pathways are involved in regulating EMT-TF expression by modulating the activity of eIF4E [72]. In breast cancer, for example, tumor cells can manipulate the expression of the Snail transcription factor and matrix metalloproteinase 3 through the MNK / eIF4E pathway. This regulation plays a role in the induction of the EMT and facilitates tumor invasion and metastasis [73]. Similarly, in the context of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, reported that the MAPK pathway promotes the expression of the Zeb1 protein by regulating phosphorylation of eIF4E. They found that this phosphorylation enhances the translation of proteins that drive the EMT in malignant tumor cells, further contributing to the aggressive nature of this cancer type. Additionally, Kelly et al. [74] found that under low oxygen conditions, eIF4E2, a homolog of eIF4E found within the hypoxic eIF4F complex, plays a distinct role in the EMT by upregulating the translation of Snail, facilitating the EMT in a manner that does not rely on the mTORC1 pathway.

However, current knowledge of the role of the EMT in facilitating tumor metastasis remains a complex and significant topic. While controversy persists, an increasing volume of evidence supports the pro-metastatic implications of the EMT [75]. Tumor metastasis is closely associated with remodeling of the extracellular matrix, which is a process that necessitates secretion of a substantial array of matrix proteins [76]. Central to this process is the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR), which is a crucial cellular mechanism for maintaining endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis. The UPR functions through the eIF2α-ATF4 signaling pathway and ensures proper folding and functionality of secreted proteins. This pathway plays an essential role in quality control, reducing the possibility of protein misfolding, which could disrupt critical cellular functions. The protein misfolding promotes the metastasis of tumor cells that undergo the EMT [77].

In addition, the EMT was also found to be associated with eIF5A2. For example, Tang DJ, et al. [78] reported that the overexpression of eIF5A2 enhances cell motility and invasiveness, which, along with a decrease in E-cadherin (a protein crucial for maintaining epithelial cell adhesion), facilitates the progression of liver metastasis. In studies involving non-small-cell lung cancer cell models, Zhu W, et al. [79] showed that down regulation of eIF5A2 expression leads to increased levels of E-cadherin and a reduction in proteins associated with poikilocytosis, attenuating the risk of metastasis. However, it is important to note that eIF5A2, unlike its counterpart eIF5A1, is primarily involved in transcriptional regulation and does not influence the synthesis of proteins [80]. It remains unclear whether the aforementioned regulation is involved in the process of translation initiation.

Non-classical translation initiation mechanisms have also been shown to be involved in the EMT. Among the various non-classical pathways, the IRES is one of the most comprehensively studied. This mechanism facilitates direct binding of ribosomes to mRNA, enabling translation initiation without the prerequisite cap-binding and scanning processes typically required in cap-dependent translation [17,81]. Evdokimova V, et al. [71] found that in breast cancer, Snail is capable of inhibiting cap-dependent translation through Y-box binding protein 1, an RNA-binding protein known for its repressive effects on translation. Consequently, this inhibition of cap-dependent translation facilitates upregulation of IRES-dependent translation, which further supports the transition to a mesenchymal-like phenotype, and contributes to tumor metastasis. Furthermore, Bera and Lewis [82] recently described increased mRNA m6A methylation modifications that occur during the EMT. Shu F, et al. [83] found that in prostate cancer cells, m6A methylation of the transcription factor nuclear factor I/B mRNA significantly enhances both the stability and the translation of this mRNA, which in turn facilitates the EMT and promotes the metastasis of tumor cells. Several other studies have shown that m6A methylation promotes translation initiation independently of the eIF4F complex and without the assistance of additional eIFs [84,85]. Investigating relationships between this specific methylation mechanism and the increased translation of EMT-specific proteins arising from elevated m6A modifications will provide critical insights into the intricate interplay between the EMT and translation initiation, which will help facilitate the development of more targeted therapeutic strategies the treatment of tumor progression.

Acquisition and maintenance of tumor stemness

The acquisition of a stemness phenotype or the transition to a more poorly differentiated state in tumor cells is frequently associated with increased malignancy and the emergence of drug resistance. Cancer stem cells possess distinctive attributes, including reduced protein synthesis and elevated ribosome synthesis, which facilitate rapid cellular reorganization during the differentiation process [86]. For example, Nguyen HG, et al. [87] found that in prostate cancer, highly malignant tumor cells exhibit a tendency to reduce overall protein synthesis through the PERK-eIF2α signaling pathway. Additionally, Zhang C, et al. [88] found that various stress conditions, including hypoxia, can induce the expression of stemness factors. Jewer M, et al. [89] reported that the phosphorylation of eIF2α, which is a defining characteristic of the ISR, facilitates the development of a stem cell phenotype in breast cancer. Furthermore, 2ʹ-O-Me modification of rRNA impacts the translational preferences observed in Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) cells, which subsequently drives the characteristics associated with the AML stem cell phenotype [90].

Translation initiation also plays a role in the maintenance of tumor stemness by facilitating the selective translation of proteins essential for supporting tumor stem cells [91]. For example, in non-small cell lung cancer, isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 enhances the stability of fragile X-related protein-1, which promotes the recruitment of the eIF4F complex. Consequently, this mechanism leads to upregulation of phospho-serine aminotransferase 1 translation, which plays a role in regulating cytosolic serine metabolism to sustain the stemness of cells [92]. Moreover, transfer RNA-modified methionyltransferase Cdk5 regulatory associated protein 1-like 1 (CDKAL1) promotes the synthesis of spalt like transcription factor 2 tumor stemness factor. This enhancement occurs through the facilitation of the assembly of the eIF4F translation initiation complex. Huang R, et al. [93] reported that the ability of CDKAL1 to promote this process maintains the stem-like characteristics of rhabdomyosarcoma tumor cells. Regulation of tumor stemness is also influenced by m6A modification [94].

In the context of HCC, METTL16 plays a role in regulating translation initiation by specifically targeting eIF3a. Xue, et al. [95] reported that his interaction affects the progression of HCC and also influences the self-renewal capacity of tumor stem cells. Additionally, Cieśla M, et al. [96] found that MYC can exhibit a reciprocal regulatory relationship with the SF3A3 splicing factor through a translation mechanism that is dependent on eIF3d. They reported that this regulatory interaction influences the stem-like characteristics observed in induced breast carcinogenesis and within cancer cells.

Results of the studies described above suggest that disrupting the translation initiation mechanisms for the formation and maintenance of tumor stemness may reduce the self-renewal ability of tumor stem cells. This intervention may also stimulate these cells to transition from a quiescent state back into an active cell cycle and enhance the effectiveness of chemotherapeutic agents, allowing a more robust strategy against resistant tumor populations.

Alterations in tumor cell metabolism

Biffo S, et al. [97] recently emphasized the role of dysregulated translational control in the abnormal metabolic processes of tumor cells [97]. MYC, PI3K, and Ras are oncogenic pathways involved in both translational and metabolic regulation. This intricate regulation allows tumor cells to utilize translation initiation, modifying their metabolic profiles to support rapid growth and survival [98]. MYC oncogenes function as potent transcription factors, playing a role in ribosomal biogenesis and in the synthesis of eIFs [99], but they also are involved in nearly every aspect of tumor metabolism [100]. In lymphomas, MYC increases the expression of the rate-limiting enzyme phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthase 2 by enhancing the activity of eIF4E, which is essential for nucleotide metabolism. Through this mechanism, MYC regulates nucleotide metabolism in lymphomas, promoting tumorigenesis and aiding the proliferation of cancer cells [101]. In contrast, the PI3K and Ras pathways regulate translation initiation through the mTOR signaling pathway, which is involved in the metabolism of lipids, nucleic acids, and carbohydrates [102]. Düvel K, et al. [103] recently showed that mTOR affects glucose metabolism in tumor cells by selectively modulating the translation of the 5'-UTR of HIF1α mRNA.

In addition to the MYC, PI3K, and Ras signaling pathways, Brina D, et al. [104] reported that eIF6 influences hepatic lipid metabolism. Specifically, Scagliola A, et al. [105] found that depletion of eIF6 in HCC cells results in a reduction in hepatic lipid accumulation and tumor progression. Other investigations have identified the roles of eIF3 in glycolysis and eIF5A2 in fatty acid metabolism within tumors [106,107]. These eIFs appear integral to the metabolic reprogramming commonly observed in cancer cells. However, the mechanisms by which tumors exploit these factors to adjust their metabolic processes in response to environmental demands and to support their growth require further investigation. The outcomes of such research could explain how tumor cells evade therapeutic pressure through metabolic reprogramming.

Translation Initiation Regulation in the Tumor Microenvironment

The complex interactions between tumor cells and various cell types within the tumor microenvironment are crucial factors in the processes of tumorigenesis and progression. Bartish, et al. [124] recently reported that translation initiation affects the activity of tumor cells and also significantly influences adjacent cells, including T cells, myeloid cells, and endothelial cells. By regulating the functions of these surrounding cells, translation initiation plays a role in the intricate network that facilitates tumor development and contributes to the challenges of drug resistance.

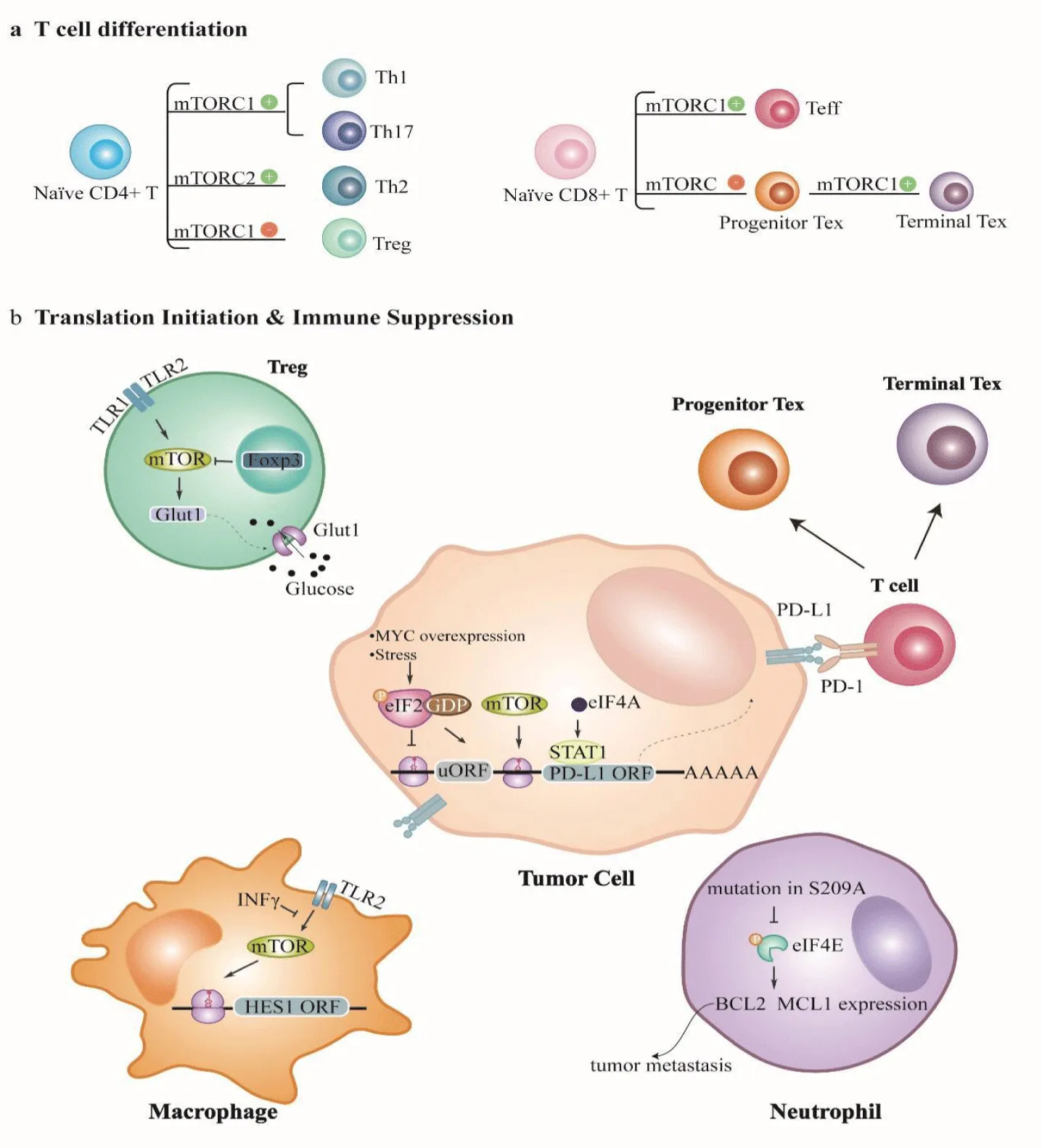

Reshaping the tumor immune microenvironment

T cells serve as critical components of anti-tumor immunity. Their differentiation, activation, and homeostasis are meticulously regulated by the process of translation initiation, particularly through the mTOR signaling pathway (Figure 2) [108]. In different microenvironments, the surrounding cellular milieu significantly influences the fate and differentiation pathways of CD4 + and CD8 + T cells by modulating protein synthesis. Empirical evidence indicates that mTOR activity is a fundamental driver of helper T cell differentiation, as it facilitates their maturation and enhances their functional capabilities [109].However, within metabolically compromised tumor microenvironments characterized by diminished nutrient availability and other adverse conditions, mTOR signaling is inhibited. This suppression necessitates an adaptive response from CD4 + T cells, which resort to DAP5 / eIF3d-mediated cap-dependent mRNA translation to promote the development and expansion of regulatory T cells (Treg) [110]. Moreover, the process of asymmetric cell division in CD8+ T cells is a key mechanism through which these cells differentiate into effector T cells and memory T cells. This complex process is regulated by the mTORC1-eIF4A signaling axis, which illustrates the importance of mTOR in orchestrating T cell differentiation within the tumor microenvironment [111].

Tumor cells have the capacity to regulate T cell function through the process of translation initiation. Comparative analyses of translation rates between T cells in the spleen and those within tumors by De Ponte Conti, et al. [112] indicate that T cells located in tumors exhibit significantly higher translation rates and increased expressions of markers indicative of exhaustion and inhibition. This phenomenon is mediated by the phosphorylation of S6K1, which acts downstream of the mTORC1 signaling pathway. Lastwika KJ, et al. [113] reported that tumor cells can enhance the expression of Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) through the activation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway, resulting in inhibition of T cell cytotoxicity. Besides the mTOR pathway, the expression of PD-L1 is also subjected to modulation by factors such as overexpression of the Myc gene, the presence of cellular stress, and the levels of eIF4A [114-117]. Collectively, these mechanisms illustrate a sophisticated regulatory environment that enables tumor cells to evade immune responses to facilitate tumor progression.

The mTOR pathway can also influence T cell metabolism [118,119]. The accumulation of adenosine serves as an inhibitor of mTORC1 activation, resulting in dysfunction of T cell metabolism and subsequent effects on their functional capabilities [120]. Treg can suppress the assembly of translation initiation complexes through the expression of the USP47 gene. This mechanism effectively reduces the translation efficiency of the c-Myc protein and the associated glycolytic metabolism in Treg cells and prevents excessive glucose metabolism, which could disrupt their homeostasis [121]. Additionally, translation initiation can affect the secretion of various T cell cytokines. For example, the secretion of chemokine ligand 5 is mediated by the p38-MNK1-eIF4E signaling pathway [122]. The chemokine ligand 5 / chemokine receptor type 5 axis is of paramount importance in the context of immune responses, as it facilitates the recruitment of immune-suppressive cells, contributing to the establishment of an immunosuppressive microenvironment [123].

The monocyte-macrophage system is a vital component of tumor innate immunity, and many studies have shown its anti-tumor effects [124]. The recruitment of monocytes to tumor tissues relies on their adhesion to the extracellular matrix, a process in which translation initiation plays a role. For example, Li F, et al. [136] found that in breast cancer, eIF4E levels are positively correlated with macrophage infiltration, suggesting that elevated levels of eIF4E may facilitate this process [129]. They also suggested that eIF4E may be linked to the M2 polarization of macrophages, which is a state often associated with poor patient prognoses. Mahoney TS, et al. [125] reported that the PI3K-mTOR-eIF4E signaling pathway mediates the expression of the urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor within myeloid cells; this receptor is crucial for the adhesion and migration of myeloid cells, as it enables them to metastasize to and infiltrate tumor sites effectively. However, the mechanism by which overexpression of eIF4E mediates macrophage infiltration remains unclear.

Tumor cells can also manipulate macrophage function through regulation of translation initiation. An example is the influence of interferon gamma, a potent cytokine that inhibits the activation of both the MNK-eIF4E and mTORC1-4E-BP-eIF4E pathways triggered by Toll-like receptor 2 signaling. Su X, et al. [126] reported that this inhibition reduces the translation of mRNA encoding the anti-inflammatory protein HES1, creating a pro-inflammatory environment. Recent studies have also revealed the distinct roles that the mTOR and MNK signaling pathways play in macrophage function. For example, Bartish M, et al. [124] reported that the mTOR pathway appears to enhance the pro-inflammatory activity of immune-stimulating macrophages, while the MNK-eIF4E pathway tends to support the functions of immune-suppressive macrophages. Beyond their roles in direct immune responses, macrophages are also crucial for antigen presentation. Hipolito showed that lipopolysaccharide-induced lysosomal expansion is mediated by mTORC1-4E-BP-dependent and mTORC1-S6K-dependent mechanisms [127].

The functions of other immune cells in the tumor microenvironment are also regulated by translation initiation. An example involves the inactivation of the key tumor suppressor glycogen synthase kinase-3, which results in elevated levels of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in breast cancer cells. This elevation initiates a series of molecular events that weakens the phosphorylation of eIF2B, leading to reduced activity of natural killer cells [128]. Similarly, the phosphorylation of eIF4E can inhibit neutrophil survival, promoting the hazardous spread of tumors to the lungs (i.e., metastasis) [30].

These studies suggest that strategic targeting of translation initiation mechanisms has the potential to transform the immune landscape of tumors. Such transformations would provide the basis for the development of new and effective strategies in immunotherapy, as illustrated in

Participation in angiogenesis

Tumors rely on angiogenesis, which is the formation of new blood vessels, to obtain oxygen and nutrients essential for their growth and survival. One of the most critical factors driving this process is Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), which functions as a key regulator in the development of blood vessels induced by tumors [129]. Unlike the majority of mRNAs that depend on cap-dependent translation for protein synthesis, VEGF mRNA features a unique IRES. This distinct characteristic allows for the enhancement of VEGF translation under hypoxic conditions when cap-dependent translation is typically reduced [130]. Zhang H, et al. [131] showed that methylation of the 5'-UTR of IRES in VEGF recruits the YTHDC2 / eIF4GI complex, leading to increased translation of VEGF and further promotion of angiogenesis.

While hypoxia and HIF signaling are well-established triggers of angiogenesis, recent studies suggest that inhibiting protein translation can also stimulate VEGF production independently of hypoxia and HIF [132]. For example, restricting amino acids can result in increased phosphorylation of eIF2α, which is a process that occurs independently of endothelial cell hypoxia and HIF, regulating VEGF expression and accelerating angiogenesis [133]. In this context, the eIF4E protein directly influences angiogenesis by mediating VEGF expression [134,135], and it also enhances the expression of matrix metalloproteinase 2. This enzyme can remodel the extracellular matrix to create a structural framework that facilitates angiogenesis [136]. However, studies of the specific mechanisms of action of eIF4E in angiogenesis are still limited. Additionally, TIE2, a pivotal receptor in the signaling pathways governing endothelial cell angiogenesis [137], and it can also undergo translation via IRES under hypoxic conditions [138].

In summary, the mechanisms that drive tumor angiogenesis through the regulation of translation initiation are more complicated than originally suggested. Further exploration of IRES-mediated angiogenesis may identify novel therapeutic targets and provide innovative insights for developing effective treatment strategies.

Regulation of tumor fibroblast plasticity

As one of the three major cell populations that significantly impact cancer progression, fibroblasts are a critical cell component of the tumor microenvironment. These cells exhibit remarkable plasticity, which allows them to alter their functions based on interactions with other cells within the tumor microenvironment [139]. Zhang L, et al. [140] showed that the regulation of translation initiation involves the malignant transformation of fibroblasts and that overexpression of any of the five eIF3 subunits (a, b, c, h, i) can induce this transformation in immortalized fibroblasts. Specifically, using experimental models of melanoma and pancreatic cancer, Verginadis II, et al. [141] revealed that stress responses can activate Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) via the ATF4 signaling pathway, promoting tumor angiogenesis and supporting tumor growth and metastasis. Li D, et al. [142] found that in gastric cancer, CAFs secrete fibroblast growth factor 2, which stimulates ribosome biogenesis and activates the eukaryotic translation initiation signaling pathway to enhance the proliferation of gastric cancer cells. Using mouse models of myocardial infarction, Ubil E, et al. [143] provided compelling evidence of the ability of fibroblasts to be reprogrammed into endothelial cells under specific conditions. Cai W, et al. [158] found that the mesenchymal-to-endothelial transition occurs in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and that it is mediated by the PERK-eIF2α-ERK1 / 2 signaling axis [150]. This transition actively promotes angiogenesis within the tumor, highlighting the complexities associated with fibroblast behavior.

These studies have elucidated the intricate relationships between regulation of translation initiation and fibroblast plasticity. This relationship extends beyond the fundamental processes of protein synthesis and also significantly influences the role of CAFs in facilitating angiogenesis.

Regulation of Translation Initiation During Therapeutic Resistance

Tumor drug resistance refers to the ability of tumor cells to withstand and adapt to therapeutic interventions through a variety of complex mechanisms, and it is a major challenge in cancer therapy. Translation initiation serves as a critical factor in tumor formation and progression, and its role in drug resistance has attracted increasing attention. When external pharmacological agents attempt to eradicate tumor cells, these cells can activate specific regulatory mechanisms associated with translation initiation. This strategic response allows them to modify protein synthesis and reshape the tumor microenvironment, promoting their survival and contributing to the development of drug resistance (Figure 3).

The eIF4F complex plays a crucial role as a regulator of translational initiation, and its dysregulation has been shown to be related to drug resistance in various tumors during tumorigenesis and development [144]. Andrieu C, et al. [145] showed that when eIF4E is artificially overexpressed in prostate cancer cells under laboratory conditions, these cells exhibit significantly enhanced resistance to the chemotherapy drug paclitaxel. Similarly, in breast cancer, both the overexpression and specific phosphorylation of eIF4E play pivotal roles in the development of resistance to tamoxifen [146].

Relevant signaling pathway reactivation represents a significant mechanism by which resistance develops in targeted therapy [147]. Specifically, the resistance observed in two well-known targeted agents, the anti-BRAF and anti-MEK pathways, depends on reactivation of the mTOR pathway. The regulatory dynamics among these three pathways lead to the formation of the eIF4F complex, which plays a vital role in protein translation and cell proliferation. Importantly, Boussemart L, et al. [148] showed that inhibition of eIF4F complex formation enhances the antitumor effects of these targeted agents, improving treatment outcomes for patients with resistant tumors.

Resistance to immunotherapy can arise from various mechanisms, which can be classified into primary and secondary categories. Primary mechanisms often involve deficiencies in the tumor’s ability to present antigens, which are essential for immune recognition. In contrast, secondary mechanisms typically encompass tumor gene mutations and the development of an immunosuppressive microenvironment that protects the tumor from immune responses [149]. Aberrant regulation of translation initiation leads to an increase in PD-L1 expression in tumor cells while simultaneously enhancing the infiltration and survival of Tregs within the tumor microenvironment,which diminishes the efficacy of immunotherapeutic interventions [150]. Recently, Hashimoto A, et al. [151] showed that inhibiting eIF4A in pancreatic cancer reduces the overexpression of oncogenes such as ARF6 and MYC, thus enhancing the effectiveness of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Additionally, eIF4A is associated with the translational upregulation of specific factors that contribute to drug resistance [144,152]. Translation initiation is a key factor in tumor dedifferentiation and transdifferentiation and also in the mechanisms underlying drug resistance in these cells. Recent research has highlighted the important function of eIF4G, which facilitates the survival of cells that have developed resistance to chemotherapy. Moreover, eIF4G is also implicated in conferring resistance to radiation therapy, particularly in cancer stem cells [153].

Recent investigations have identified the association between the stress response and drug resistance in tumors. Specifically, an increase in the phosphorylation level of eIF2α has been documented in various drug-resistant tumors [154,155]. For example, Palam, et al. [156] reported that pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma shows gemcitabine resistance mediated by upregulation of the Nupr1anti-apoptotic factor, which occurs via activation of the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 signaling pathway. Conversely, She, et al. [157] suggested that activation of the PERK-eIF2α axis may induce apoptosis, providing a potential strategy for mitigating tumor resistance. The cytotoxic effects of paclitaxel, a widely used chemotherapeutic agent, are partially mediated by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Notably, the concurrent application of PERK agonists with paclitaxel has demonstrated efficacy in overcoming paclitaxel resistance in breast cancer [158].

The activation of the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 signaling pathway can result in a variety of outcomes regarding tumor drug resistance. Therefore, it is important to investigate the role of this specific signaling pathway as well as the unique molecular characteristics inherent to each tumor within the context of drug resistance studies. This approach emphasizes the critical importance of precision therapy, which aims to tailor treatment strategies to the individual molecular profiles of tumors for enhanced patient efficacy.

In addition to their role in regulating eIFs, tumor cells can alter both the production and function of ribosomes, which allows them to effectively evade the harmful effects of anticancer treatments [48]. Gambardella reported that in HER2-amplified gastric cancer, drug-resistant tumor cells exhibit a marked increase in the translation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 [167]. They found that this increase is driven by the activation of the PI3K / AKT / mTOR / RPS6 signaling pathway, which is a complex network that is essential for mediating drug resistance within tumors. Chen L-b, et al. [170] found that the METTL5 and TRNA methyltransferase activator subunit 11-2 proteins are also involved in this process [55]. They reported that these proteins facilitate the methylation of 18S rRNA, which is a modification that disrupts the assembly of 80S ribosomes, and that this disruption selectively affects protein translation, creating a favorable environment for nasopharyngeal carcinogenesis and enhancing chemoresistance [55].

Other studies have highlighted the significant role of non-classical translation mechanisms in the phenomenon of tumor resistance. Specifically, Muranen T, et al. [159] reported that inhibitors of the PI3K / mTOR signaling pathway induce a cellular stress response through IRES, contributing to the development of drug resistance in ovarian cancer. Additionally, Chen, et al. [160] showed that m6A-mediated methylation modifications are upregulated across various types of drug-resistant tumors, indicating a potential common mechanism of resistance. Shen S, et al. [161] found that m6A-mediated methylation modifications are selectively translated in melanoma through an eIF4A-dependent mechanism, contributing to the resistance of tumors to pharmacological treatment.

Translation initiation directly influences tumor cells, contributes to their ability to develop resistance, and also affects the tumor microenvironment, which can further promote drug resistance, particularly to immunotherapy [108]. For example, Han D, et al. [162] showed that deletion of the m6A methylation-binding protein YTHDF1 in dendritic cells enhances the efficacy of PD-L1 immunotherapy. Additionally, Duluc C, et al. [163] reported that inhibiting the mTOR signaling pathway in CAFs within pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma diminishes the secretion of proteins that promote drug resistance and that this reduction decreases the tumor’s ability to evade treatment and improves the effectiveness of gemcitabine.

In summary, the regulation of translation initiation contributes to drug sensitivity in tumors and plays a role in developing drug resistance by altering the tumor microenvironment. Research indicates that combining translation initiation inhibitors with established antitumor drugs can enhance therapeutic effectiveness, as demonstrated by promising results from various in vivo and in vitro preclinical studies [164,165]. Currently, numerous clinical trials are underway to investigate the efficacy of combining mRNA translation inhibitors with a range of anticancer agents (Table 1). Innovative strategies that specifically target the regulation of translation initiation may offer new and effective avenues for tumor treatment.

| Table 1: Clinical studies of the combined application of mRNA translation inhibitors and anticancer drugs. | ||||||||

| Target | Agent | Tumor | Clinical Trail | Phase | State | ORR | PFS(months) | OS(months) |

| PI3K/AKT/mTOR | Ridaforolimus + MK-0752 | HNSCC | NCT01295632 | I | Completed | 18% | / | / |

| Fulvestrant versus Fulvestrant + Sapanisertib(daily) versus Fulvestrant + Sapanisertib(weekly) | Breast | NCT02756364 | II | Completed | 10.9% versus 21.3% versus 12.8% | 3.5 (95% CI 1.9-5.6) versus 7.2 (95% CI 3.9 - 10.6) versus 5.6 (95% CI 4.1 - 9.0) | / | |

| MLN0128+ Paclitaxel + Trastuzumab | solid tumors | NCT01351350 | I | Completed | 14.80% | / | / | |

| Everolimus + Letrozole | ovarian | NCT02283658 | II | Completed | 16% | 3.9 (95% CI 2.8 -1 1) | 13 | |

| Everolimus + Exemestrane versus Placebo + Exemestrane | Breast | NCT00863655 | III | Completed | / | 6.9 (95% CI 6.4 - 8.1) versus 2.8 (95% CI 2.7 - 4.1) | 31.0 mo (95% CI 28.0 - 34.6) versus 26.6 (95% CI 22.6 - 33.1) | |

| Everolimus + Rituximab | lymphoma | NCT00869999 | II | Completed | 38% (90% CI 21 - 56%) | 2.9 (90% CI 1.8 - 3.8) | 8.6 (90% CI 4.9 - 16.3) | |

| Gedatolisib + Paclitaxel + Carboplatin | solid tumors | NCT03243331 | I | Completed | 65% | 6.4 (95% CI 4.6 - 11.1) | / | |

| Prexasertib + Samotolisib | solid tumors | NCT02124148 | Ib | Completed | 15% | / | / | |

| Samotolisib + Enzalutamide versus placebo+enzalutamide | prostate | NCT02407054 | Ib / II | Completed | / | 3.8 versus 2.8 | / | |

| voxtalisib + erlotinib | solid tumors | NCT00777699 | I | Completed | SD: 37.5% | / | / | |

| Voxtalisib + rituximab versus voxtalisib + rituximab + bendamustine | B-cell malignancies | NCT01410513 | Ib | Completed | 49% | 7.5 | / | |

| Voxtalisib + Pimasertib | solid tumors | NCT01390818 | Ib | Completed | 5% | / | / | |

| Voxtalisib + Pimasertib versus Pimasertib | ovarian | NCT01936363 | II | Completed | 9.4%(80% CI 3.5 - 19.7) versus 12.1%(80% CI 5.4 - 22.8) | 10.0(80% CI 7.4 - 10.4) versus 7.2(80% CI 5.1 - ) | / | |

| Sapanisertib + Osimertinib versus Alisertib + Osimertinib | NSCLC | NCT04479306 | Ib | Active, not recruiting | ||||

| Sapanisertib + Telaglenastat | NSCLC | NCT04250545 | Ib/II | Active, not recruiting | ||||

| MNK | Tomivosertib + PD-1 / PD - L1 Inhibitor | solid tumors | NCT03616834 | II | Active, not recruiting | |||

| Tomivosertib + Avelumab versus Tomivosertib | colorectal | NCT03258398 | II | Active, not recruiting | ||||

| Tomivosertib + Pembrolizumab | NSCLC | NCT04622007 | II | Active, not recruiting | ||||

| eIF4E | 4E ASO + Irinotecan | colorectal | NCT01675128 | I / II | Completed | / | 1.9 | 8.3 |

| Ribavirin + Ara-C | AML | NCT01056523 | I | Completed | 23.80% | / | / | |

| ISIS EIF4E Rx + Paclitaxel + Carboplatin versus Paclitaxel + Carboplatin | NSCLC | NCT01234038 | Ib / II | Active, not recruiting | ||||

| eIF4A | Zotatiffin + Sotorasib/Zotatiffin + Fulvestrant/Zotatiffin + Abemaciclib/Zotatiffin + Trastuzumab | solid tumors | NCT04092673 | I / II | Recruiting | |||

| HNSCC: Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma; NSCLC: Non Small Cell Lung Cancer; AML: Acute Myeloid Leukemia; ORR: Overall Response Rate; PFS: Progression-Free Survival; OS: Overall Survival. | ||||||||

Conclusion

The rapid and uncontrolled proliferation of tumor cells necessitates a significant increase in protein synthesis, with translation initiation serving as a critical step that influences the efficiency of this process. Tumor cells effectively enhance their overall protein synthesis by upregulating and activating specific eIFs. Additionally, tumor cells can selectively increase the synthesis of specific proteins by employing these factors, such as eIF4E and eIF4G, along with using non-cap-dependent translation initiation mechanisms. This targeted approach to protein synthesis enables tumor cells to fulfill their unique growth requirements, including malignant transformation, the process by which normal cells become cancerous, as well as the complex development of the tumor microenvironment that supports their survival and proliferation.

In recent years, translation-omics (translatomics) has emerged as a promising technology for studying translational regulation mechanisms in tumors [166]. By leveraging ribosome profiling techniques (e.g., Ribo-seq), translatomics facilitates a comprehensive understanding of which mRNAs are selectively translated in tumor cells and how translation efficiency changes. This approach provides new perspectives for understanding how tumor cells regulate the translation of specific proteins to adapt to environmental pressures and therapeutic stress. When paired with RNA sequencing, translatomics can effectively determine whether gene expression is primarily regulated at the transcriptional or translational level. Zeng H, et al. [167] developed a novel translatomics sequencing method, RIBOmap, which enables genome-wide analysis of mRNA translation with spatial and single-cell resolution. In the future, it is reasonable to envision that ribosome profiling technologies, particularly those designed for (spatially resolved) single-cell translatomics studies, will advance future cancer research by identifying novel translational events in malignant cells.

In terms of clinical applications, the diversity of translational and regulatory factors observed within tumors, combined with the significant correlation between these factors and prognoses across different types of tumors, suggests that they may serve as promising new predictive markers. These markers could play a critical role in assessing tumor prognosis and determining how effectively a tumor responds to various therapeutic interventions [168-170]. Despite extensive research showing a strong correlation between eIFs and poor cancer prognoses, these metrics have not been widely implemented in clinical settings to predict patient outcomes or monitor disease progression. This may be due to the fundamental nature of protein translation, which is a cellular process that is often upregulated by translation-related factors in various physiological situations, such as inflammation and tissue repair. Such biological upregulation can obscure the effectiveness of these factors in accurately predicting tumor development. Additionally, current studies tend to focus on the expression levels of eIFs within tumor tissues, with limited attention given to how these factors are expressed in the blood and their potential correlation with prognoses. Because consistent and long-term monitoring is essential for evaluating tumors, blood tests are a practical and convenient solution for clinical applications, making them an ideal choice for ongoing patient monitoring and assessment of disease progression.

Preclinical and clinical studies have explored the direct targeting of eIFs, yielding promising results [171,172]. For example, Truitt ML, et al. [5] showed that protein synthesis remains largely unchanged, even when levels of the key eIF4E are reduced by 50% in normal cells [24]. This significant finding suggests a valuable and safe therapeutic range, which indicates that targeting eIFs could be a viable therapeutic strategy without a negative impact on normal cellular protein production. The mTOR inhibitors, which specifically target translation initiation, constitute the only class of drugs currently approved for clinical use. Nevertheless, these drugs have encountered therapy resistance in actual clinical applications, which poses challenges to their efficacy in treating various conditions [8].

Resistance to targeted therapy frequently arises from the intricate heterogeneity within tumors and the tumor cells’ remarkable ability to adapt to their environments. The complicated regulation of translation initiation enhances this adaptability; therefore, inhibiting a single pathway does not entirely disrupt malignant translation, as tumors frequently activate alternative pathways during their ongoing evolution. Additionally, the roles of mTOR molecules in cellular processes are very intricate, and their inhibitors produce effects on translation initiation that lack specificity. Consequently, there is an urgent need for further research to effectively leverage the mechanisms of translation initiation regulation in tumor treatment.

Faced with therapeutic pressure, tumor cells demonstrate a notable capacity to modify their protein synthesis. They can generate proteins that confer resistance, enabling them to survive and thrive despite drug intervention. This dynamic ability contributes to the development of drug resistance and poses significant challenges to cancer treatment. Despite substantial research on the use of translation initiation inhibitors alongside conventional antitumor agents, there remains a notable absence of definitive clinical evidence that substantiates the effectiveness of translation initiation regulation in overcoming drug resistance. It is crucial to further investigate how the modulation of translation initiation influences tumor heterogeneity and to identify the adaptive strategies of translation initiation that tumors employ in response to therapy stress. This approach is crucial, as it emphasizes the pivotal role that translation initiation plays in the emergence and development of drug resistance. Moreover, understanding the intricate and multifaceted nature of the molecular pathways involved will provide exciting opportunities for innovation. By exploring and developing novel combination therapies that simultaneously target multiple pathways, we can enhance the effectiveness of existing drug regimens and potentially improve the overall efficacy of tumor-killing treatments and offer new hope in the fight against resilient cancer cells.

In conclusion, this in-depth examination of the translation initiation mechanism revealed crucial insights into the molecular foundations of tumorigenesis and cancer development. This collection of information increases our understanding and also establishes a robust theoretical framework for the future development of antitumor agents. It also promises to enhance therapeutic strategies for cancers and spur advancements in precision medicine. Although current clinical evidence for direct application is still limited, the ongoing evolution of research and innovations in personalized therapies suggest that regulation of translation initiation may soon emerge as an important approach in tumor diagnosis and treatment. This novel approach could provide more effective and safer treatment options, offering renewed hope for cancer patients.

Acknowledgement

All Figures were created with adobe illustrator.

Author's Contributions

Shi-Lin Lin: Writing – original draft, Investigation. Yue Wang: Writing – original draft, Investigation Jia Fan: Writing – review & editing. Chao Gao: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Ai-Wu Ke: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

The Conflict-of-Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Information

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82403999).

References

- Schwanhäusser B, Busse D, Li N, Dittmar G, Schuchhardt J, Wolf J, Chen W, Selbach M. Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature. 2011 May 19;473(7347):337-42. doi: 10.1038/nature10098. Erratum in: Nature. 2013 Mar 07;495(7439):126-7. doi: 10.1038/nature11848. PMID: 21593866

- Gray NK, Wickens M. Control of translation initiation in animals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:399-458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.399. PMID: 9891789.

- Jia X, He X, Huang C, Li J, Dong Z, Liu K. Protein translation: biological processes and therapeutic strategies for human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024 Feb 23;9(1):44. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01749-9. PMID: 38388452; PMCID: PMC10884018.

- Song P, Yang F, Jin H, Wang X. The regulation of protein translation and its implications for cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021 Feb 18;6(1):68. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00444-9. PMID: 33597534; PMCID: PMC7889628.

- Truitt ML, Ruggero D. New frontiers in translational control of the cancer genome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016 Apr 26;16(5):288-304. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.27. Erratum in: Nat Rev Cancer. 2017 Apr 24;17(5):332. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.30. PMID: 27112207; PMCID: PMC5491099.

- Murugan AK. mTOR: Role in cancer, metastasis and drug resistance. Semin Cancer Biol. 2019 Dec;59:92-111. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.07.003. Epub 2019 Aug 10. PMID: 31408724.

- Malka-Mahieu H, Newman M, Désaubry L, Robert C, Vagner S. Molecular Pathways: The eIF4F Translation Initiation Complex-New Opportunities for Cancer Treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Jan 1;23(1):21-25. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2362. Epub 2016 Oct 27. PMID: 27789529.

- Hua H, Kong Q, Zhang H, Wang J, Luo T, Jiang Y. Targeting mTOR for cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2019 Jul 5;12(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0754-1. PMID: 31277692; PMCID: PMC6612215.

- Petrychenko V, Yi SH, Liedtke D, Peng BZ, Rodnina MV, Fischer N. Structural basis for translational control by the human 48S initiation complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2025 Jan;32(1):62-72. doi: 10.1038/s41594-024-01378-4. Epub 2024 Sep 17. PMID: 39289545; PMCID: PMC11746136.

- Brito Querido J, Sokabe M, Kraatz S, Gordiyenko Y, Skehel JM, Fraser CS, Ramakrishnan V. Structure of a human 48S translational initiation complex. Science. 2020 Sep 4;369(6508):1220-1227. doi: 10.1126/science.aba4904. PMID: 32883864; PMCID: PMC7116333.

- She R, Luo J, Weissman JS. Translational fidelity screens in mammalian cells reveal eIF3 and eIF4G2 as regulators of start codon selectivity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023 Jul 7;51(12):6355-6369. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad329. PMID: 37144468; PMCID: PMC10325891.

- Lai WC, Zhu M, Belinite M, Ballard G, Mathews DH, Ermolenko DN. Intrinsically Unstructured Sequences in the mRNA 3' UTR Reduce the Ability of Poly(A) Tail to Enhance Translation. J Mol Biol. 2022 Dec 30;434(24):167877. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2022.167877. Epub 2022 Nov 8. PMID: 36368412; PMCID: PMC9750134.

- Wang J, Shin BS, Alvarado C, Kim JR, Bohlen J, Dever TE, Puglisi JD. Rapid 40S scanning and its regulation by mRNA structure during eukaryotic translation initiation. Cell. 2022 Nov 23;185(24):4474-4487.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.10.005. Epub 2022 Nov 4. PMID: 36334590; PMCID: PMC9691599.

- Ceci M, Gaviraghi C, Gorrini C, Sala LA, Offenhäuser N, Marchisio PC, Biffo S. Release of eIF6 (p27BBP) from the 60S subunit allows 80S ribosome assembly. Nature. 2003 Dec 4;426(6966):579-84. doi: 10.1038/nature02160. PMID: 14654845.

- Pestova TV, Lomakin IB, Lee JH, Choi SK, Dever TE, Hellen CU. The joining of ribosomal subunits in eukaryotes requires eIF5B. Nature. 2000 Jan 20;403(6767):332-5. doi: 10.1038/35002118. PMID: 10659855.

- Jackson RJ, Hellen CU, Pestova TV. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010 Feb;11(2):113-27. doi: 10.1038/nrm2838. PMID: 20094052; PMCID: PMC4461372.

- Johnson AG, Grosely R, Petrov AN, Puglisi JD. Dynamics of IRES-mediated translation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2017 Mar 19;372(1716):20160177. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0177. PMID: 28138065; PMCID: PMC5311923.

- Roiuk M, Neff M, Teleman AA. eIF4E-independent translation is largely eIF3d-dependent. Nat Commun. 2024 Aug 6;15(1):6692. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-51027-z. PMID: 39107322; PMCID: PMC11303786.

- Brito Querido J, Díaz-López I, Ramakrishnan V. The molecular basis of translation initiation and its regulation in eukaryotes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024 Mar;25(3):168-186. doi: 10.1038/s41580-023-00624-9. Epub 2023 Dec 5. PMID: 38052923.

- Rubio A, Garland GD, Sfakianos A, Harvey RF, Willis AE. Aberrant protein synthesis and cancer development: The role of canonical eukaryotic initiation, elongation and termination factors in tumorigenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022 Nov;86(Pt 3):151-165. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.04.006. Epub 2022 Apr 26. PMID: 35487398.

- Sehrawat U. Exploiting Translation Machinery for Cancer Therapy: Translation Factors as Promising Targets. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Oct 9;25(19):10835. doi: 10.3390/ijms251910835. PMID: 39409166; PMCID: PMC11477148.

- Gao X, Jin Y, Zhu W, Wu X, Wang J, Guo C. Regulation of Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 4E as a Potential Anticancer Strategy. J Med Chem. 2023 Sep 28;66(18):12678-12696. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00636. Epub 2023 Sep 19. PMID: 37725577.

- Liu X, Vaidya AM, Sun D, Zhang Y, Ayat N, Schilb A, Lu ZR. Role of eIF4E on epithelial-mesenchymal transition, invasion, and chemoresistance of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2020 Mar;40(2-3):126-131. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12011. Epub 2020 Mar 18. PMID: 32189455; PMCID: PMC7144414.

- Truitt ML, Conn CS, Shi Z, Pang X, Tokuyasu T, Coady AM, Seo Y, Barna M, Ruggero D. Differential Requirements for eIF4E Dose in Normal Development and Cancer. Cell. 2015 Jul 2;162(1):59-71. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.049. Epub 2015 Jun 18. PMID: 26095252; PMCID: PMC4491046.

- Brina D, Ponzoni A, Troiani M, Calì B, Pasquini E, Attanasio G, Mosole S, Mirenda M, D'Ambrosio M, Colucci M, Guccini I, Revandkar A, Alajati A, Tebaldi T, Donzel D, Lauria F, Parhizgari N, Valdata A, Maddalena M, Calcinotto A, Bolis M, Rinaldi A, Barry S, Rüschoff JH, Sabbadin M, Sumanasuriya S, Crespo M, Sharp A, Yuan W, Grinu M, Boyle A, Miller C, Trotman L, Delaleu N, Fassan M, Moch H, Viero G, de Bono J, Alimonti A. The Akt/mTOR and MNK/eIF4E pathways rewire the prostate cancer translatome to secrete HGF, SPP1 and BGN and recruit suppressive myeloid cells. Nat Cancer. 2023 Aug;4(8):1102-1121. doi: 10.1038/s43018-023-00594-z. Epub 2023 Jul 17. PMID: 37460872; PMCID: PMC11331482.

- Yang M, Lu Y, Piao W, Jin H. The Translational Regulation in mTOR Pathway. Biomolecules. 2022 Jun 8;12(6):802. doi: 10.3390/biom12060802. PMID: 35740927; PMCID: PMC9221026.

- Panwar V, Singh A, Bhatt M, Tonk RK, Azizov S, Raza AS, Sengupta S, Kumar D, Garg M. Multifaceted role of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling pathway in human health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023 Oct 2;8(1):375. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01608-z. PMID: 37779156; PMCID: PMC10543444.

- Ueda T, Watanabe-Fukunaga R, Fukuyama H, Nagata S, Fukunaga R. Mnk2 and Mnk1 are essential for constitutive and inducible phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 4E but not for cell growth or development. Mol Cell Biol. 2004 Aug;24(15):6539-49. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6539-6549.2004. PMID: 15254222; PMCID: PMC444855.

- Huang XB, Yang CM, Han QM, Ye XJ, Lei W, Qian WB. MNK1 inhibitor CGP57380 overcomes mTOR inhibitor-induced activation of eIF4E: the mechanism of synergic killing of human T-ALL cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018 Dec;39(12):1894-1901. doi: 10.1038/s41401-018-0161-0. Epub 2018 Oct 8. PMID: 30297804; PMCID: PMC6289382.

- Robichaud N, Hsu BE, Istomine R, Alvarez F, Blagih J, Ma EH, Morales SV, Dai DL, Li G, Souleimanova M, Guo Q, Del Rincon SV, Miller WH Jr, Ramón Y Cajal S, Park M, Jones RG, Piccirillo CA, Siegel PM, Sonenberg N. Translational control in the tumor microenvironment promotes lung metastasis: Phosphorylation of eIF4E in neutrophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018 Mar 6;115(10):E2202-E2209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717439115. Epub 2018 Feb 20. PMID: 29463754; PMCID: PMC5877985.

- Li M, Lou L, Ren L, Li C, Han R, Jiang J, Qi L, Jiang Y. EIF4G2 Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression via IRES-dependent PLEKHA1 Translation Regulation. J Proteome Res. 2024 Oct 4;23(10):4553-4566. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.4c00457. Epub 2024 Aug 30. PMID: 39213495.

- Weber R, Kleemann L, Hirschberg I, Chung MY, Valkov E, Igreja C. DAP5 enables main ORF translation on mRNAs with structured and uORF-containing 5' leaders. Nat Commun. 2022 Dec 6;13(1):7510. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-35019-5. PMID: 36473845; PMCID: PMC9726905.

- Dorrello NV, Peschiaroli A, Guardavaccaro D, Colburn NH, Sherman NE, Pagano M. S6K1- and betaTRCP-mediated degradation of PDCD4 promotes protein translation and cell growth. Science. 2006 Oct 20;314(5798):467-71. doi: 10.1126/science.1130276. PMID: 17053147.

- Holz MK, Ballif BA, Gygi SP, Blenis J. mTOR and S6K1 mediate assembly of the translation preinitiation complex through dynamic protein interchange and ordered phosphorylation events. Cell. 2005 Nov 18;123(4):569-80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.024. PMID: 16286006.

- Din FV, Valanciute A, Houde VP, Zibrova D, Green KA, Sakamoto K, Alessi DR, Dunlop MG. Aspirin inhibits mTOR signaling, activates AMP-activated protein kinase, and induces autophagy in colorectal cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2012 Jun;142(7):1504-15.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.050. Epub 2012 Mar 6. PMID: 22406476; PMCID: PMC3682211.

- Quintas A, Harvey RF, Horvilleur E, Garland GD, Schmidt T, Kalmar L, Dezi V, Marini A, Fulton AM, Pöyry TAA, Cole CH, Turner M, Sawarkar R, Chapman MA, Bushell M, Willis AE. Eukaryotic initiation factor 4B is a multi-functional RNA binding protein that regulates histone mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024 Oct 28;52(19):12039-12054. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae767. PMID: 39225047; PMCID: PMC11514447.

- Wu D, Matsushita K, Matsubara H, Nomura F, Tomonaga T. An alternative splicing isoform of eukaryotic initiation factor 4H promotes tumorigenesis in vivo and is a potential therapeutic target for human cancer. Int J Cancer. 2011 Mar 1;128(5):1018-30. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25419. PMID: 20473909.