2025 July 16;6(7):880-883. doi: 10.37871/jbres2142.

Case Presentation: Corticosteroids as the treatment of Left Hypoglossal Nerve Paralysis in a 35-Year-Old Man Following a Jiu Jitsu Training Maneuver

Zacharias Kalentakis*

Abstract

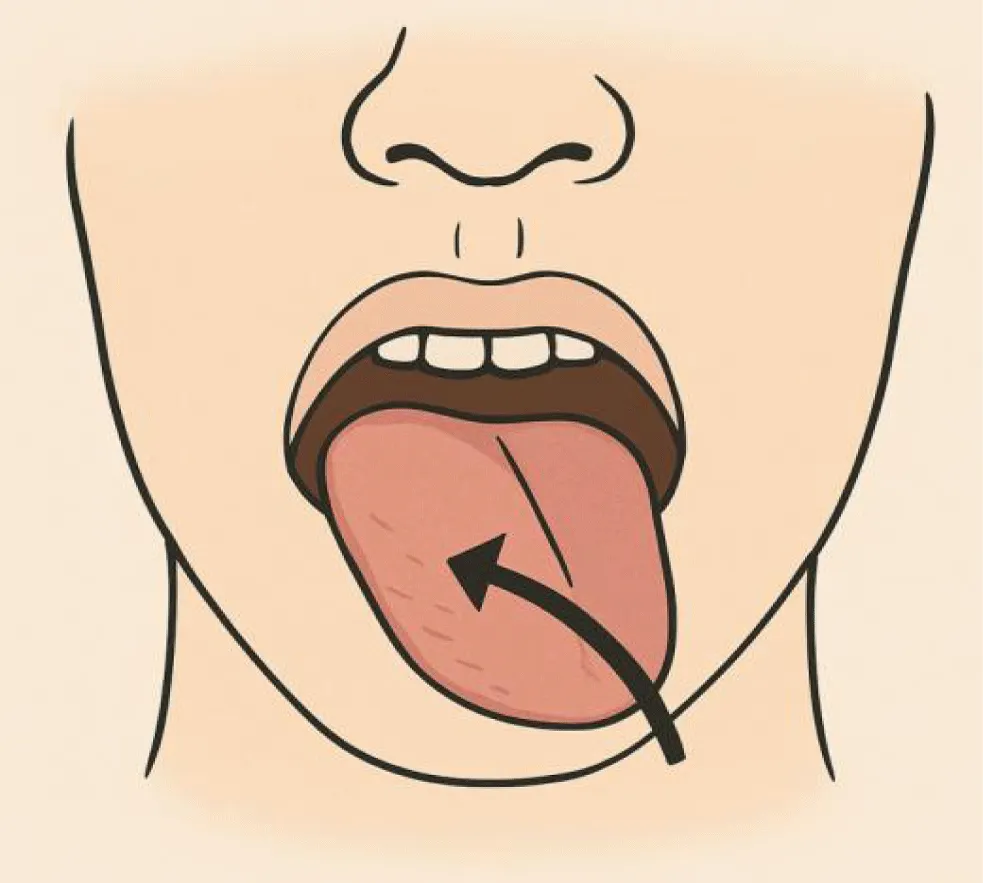

This case report describes a rare instance of isolated left hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII) paralysis in a 35-year-old male following a jiu jitsu training session. The patient presented with acute-onset dysarthria and tongue deviation to the left. Physical examination revealed unilateral tongue weakness without other neurological deficits. Imaging studies ruled out structural lesions, suggesting a traumatic neuropraxia mechanism. The patient showed significant improvement with conservative management (corticosteroids and antibiotics) over 8 weeks. Isolated hypoglossal nerve palsy is rare and often prompts evaluation for neoplastic, vascular, infectious, or traumatic causes. We report a unique case of post-traumatic hypoglossal neuropathy following neck manipulation during martial arts activity, with no identifiable lesion on imaging. This case highlights the importance of recognizing hypoglossal nerve injuries in contact sports and the need for proper neck positioning during grappling maneuvers. Moreover, anatomical, pathophysiological, and therapeutic elements of hypoglossal nerve injuries with emphasis on sports-related trauma are analyzed.

Case Presentation

History of present illness

A 35-year-old previously healthy right-handed male with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department with a 3-hour history of slurred speech and difficulty manipulating food in his mouth. Symptoms of dysarthria began shortly after a Brazilian jiu jitsu training session where he sustained a forced hyperextension and lateral flexion of the neck while attempting to escape a rear naked choke hold. He denied loss of consciousness, neck pain, or sensory symptoms,any preceding trauma, infection, or neurological symptoms.

There was no history of chronic medical conditions, substance use, or recent travel. Neurological examination revealed isolated paralysis of the left hypoglossal nerve, characterized by tongue deviation and weakness. No other cranial nerve deficits or motor/sensory abnormalities were observed (Table 1).

| Cranial Nerve | Findings |

| XII (Hypoglossal) | Marked deviation of protruded tongue to the left Left-sided tongue atrophy Fasciculations on left tongue surface Weakness on left tongue protrusion and lateral movement |

| Other Cranial Nerves | Normal |

Ear, nose, and throat examination, including flexible laryngoscopy, was unremarkable. Non-contrast Computed Tomography (CT) of the head and neck showed no acute findings. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the brain and brainstem, performed to evaluate for potential compressive, vascular, or demyelinating pathology, but was also unremarkable.

The patient was admitted for observation and received intravenous corticosteroids (250mg Hydrocortisone S: 1x2, 8mg Dexamethasone S: 1x1) and broad-spectrum antibiotics (1g Cefoxitin S: 1x3) for three days. He was discharged with an additional seven-day course of oral corticosteroids (2mg/5ml oral sol Dexamethasone) and antibiotics (200mg tab Cefditoren S: 1x2).

At one-month follow-up, the patient reported gradual improvement in speech, articulation, and tongue sensation. However, residual reduction in tongue mobility persisted, consistent with partial recovery of hypoglossal nerve function. Motor examination revealed normal strength in all extremities (5/5). The sensory examination was intact to light touch, pinprick, and vibration. The reflexes were 2+ and symmetric. Cerebellar testing was normal. No meningeal signs were present.

Diagnostic studies

MRI of the brain and cervical spine with contrast revealed no infarction, mass lesion, or compressive pathology along the hypoglossal nerve's course. CT angiography of the neck vessels showed no evidence of dissection or vascular abnormalities.

- A thorough diagnostic approach to hypoglossal nerve palsy should include:

- Detailed history focusing on recent trauma, procedures, or systemic symptoms

- Comprehensive neurological examination with emphasis on cranial nerve assessment

- MRI of the brain and skull base with special attention to the hypoglossal canal

- CT angiography if vascular causes are suspected

Management and outcome

The patient received intravenous corticosteroids (Hydrocortisone 250 mg twice daily and Dexamethasone 8 mg once daily) and broad-spectrum antibiotics (Cefoxitin 1 g three times daily) during the initial 3-day hospital admission. Upon discharge, he continued a 7-day course of oral corticosteroids (Dexamethasone 2 mg/5 ml solution) and oral antibiotics (Cefditoren 200 mg twice daily).

While imaging and clinical evaluation revealed no signs of infection, antibiotics were administered empirically. This decision was based on the possibility of an occult infectious or inflammatory etiology contributing to cranial nerve dysfunction. Although no systemic signs of infection were identified, empirical antibiotic coverage was used as a precautionary measure, particularly given the acute neurologic presentation and potential for post-viral or localized infectious neuritis. In retrospect, corticosteroids were likely the key therapeutic agent, and the antibiotics may have been unnecessary.

The patient also initiated speech therapy and tongue-strengthening exercises as part of conservative management. At the 8-week follow-up, he had recovered approximately 80% of tongue function, with persistent mild dysarthria. By 12 weeks, he had achieved complete clinical recovery (Figure 1).

Anatomy of the hypoglossal nerve

The hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII) is a purely motor nerve that innervates all intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the tongue except the palatoglossus (innervated by the vagus nerve). It originates from the hypoglossal nucleus in the medulla and exits the skull through the hypoglossal canal. The nerve then descends between the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein before looping forward to supply the tongue muscles.

Etiology of hypoglossal nerve palsy

Isolated hypoglossal nerve palsy is rare, with reported causes including:

- Trauma: Penetrating injuries, cervical hyperextension/flexion injuries, intubation trauma, dental procedures

- Neoplastic: Skull base tumors, metastatic lesions, carotid body tumors

- Vascular: Carotid artery dissection, aneurysm, vertebrobasilar ischemia

- Infectious: Meningitis, skull base osteomyelitis

- Iatrogenic: Radiation therapy, surgical complications

- Idiopathic: Approximately 25% of cases

Sports-related hypoglossal nerve injuries

While rare, several cases of hypoglossal nerve injury related to sports activities have been reported:

- Martial arts (jiu jitsu, judo) - forced neck hyperextension during choke holds

- Weightlifting - compression from heavy barbell placement

- Rugby - direct trauma to the neck

- Diving - rapid deceleration injuries

The proposed mechanism in martial arts involves stretching or compression of the nerve as it passes between the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein during forced neck movements.

Treatment depends on the underlying etiology:

- Traumatic: Conservative management with speech therapy; most cases resolve within 3-6 months

- Compressive lesions: Surgical decompression when indicated

- Infectious: Appropriate antimicrobial therapy

- Vascular: Anticoagulation for dissection, surgical intervention for aneurysms

Prognosis is generally good for traumatic neuropraxia, with most patients showing significant improvement within 2-3 months. Complete recovery may take up to 12 months in some cases.

Discussion

In the absence of radiologic or ENT pathology, idiopathic or traumatic neuropathy remains the most plausible diagnosis. The clinical course and response to corticosteroids are consistent with a self-limited inflammatory or traumatic process. Antibiotic use, although empirical, was likely unnecessary in retrospect.

This case stands for an unusual but important neurological complication of martial arts training. The mechanism likely involved stretching of the hypoglossal nerve during the forced neck hyperextension and lateral flexion while attempting to escape the choke hold. The absence of other neurological deficits and normal imaging findings support a diagnosis of isolated hypoglossal nerve neuropraxia.Neuropraxia, a transient conduction block without axonal disruption, is a likely mechanism given the acute onset and gradual recovery.

The hypoglossal nerve has a long extracranial course and is vulnerable to injury from excessive neck rotation, hyperextension, or compression. The hypoglossal nerve is particularly vulnerable to stretch injuries in its extracranial course where it passes between the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein. During neck hyperextension and lateral flexion, these vascular structures can compress or stretch the nerve against surrounding tissues.

This case highlights several important clinical points:

- Sports medicine practitioners should be aware of this potential complication in contact sports involving neck maneuvers

- Proper technique in escaping choke holds should emphasize minimizing neck hyperextension

- Acute onset of dysarthria following neck trauma should prompt evaluation for cranial nerve injuries

- Most traumatic cases have excellent prognosis with conservative management

Future research should focus on developing preventive strategies and optimal rehabilitation protocols for athletes with cranial nerve injuries.

Differential Diagnosis

An isolated hypoglossal nerve palsy is rare and has a limited differential. Given the normal imaging, no ENT abnormalities, and no systemic illness, the most likely causes include:

Traumatic neuropraxia (Stretch Injury)

Most likely diagnosis in this context. Hypoglossal nerve could have been stretched or compressed during neck manipulation or strain in Jiu Jitsu. This can occur without visible damage on MRI or CT. Explains the sudden onset and gradual improvement over weeks (typical for neuropraxia).

Idiopathic cranial neuropathy

Similar to Bell’s palsy but affecting CN XII. It is a rare diagnosis of exclusion. Response to corticosteroids supports inflammatory/idiopathic mechanism.

Infectious or post-infectious neuropathy

While no systemic infection was noted, mild viral neuritis could cause isolated CN palsy. The use of antibiotics and steroids may have helped an unrecognized viral or immune-mediated etiology.

Compressive lesion (Unlikely here)

Tumors or vascular lesions at the skull base can cause CN XII palsy. Ruled out by normal MRI and laryngoscopy.

Additional considerations

- The normal ENT exam and laryngoscopy help rule out base of tongue or pharyngeal lesions.

- Antibiotics may have been given empirically; the benefit likely came from the steroids.

- Lingual weakness and persistent reduced motion are consistent with partial nerve recovery post-neuropraxia.

Conclusion

Isolated hypoglossal nerve palsy can result from mechanical neck trauma during contact sports such as Jiu Jitsu. Recognition of this rare presentation is essential to avoid unnecessary investigations. Conservative treatment with corticosteroids and observation may be proper in select cases with no structural abnormalities [1-7].

References

- Kim JS, Lee JH, Lee MC. Patterns of sensory dysfunction in lateral medullary infarction. Clinical-MRI correlation. Neurology. 1997 Dec;49(6):1557-63. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.6.1557. PMID: 9409346.

- Keane JR. Twelfth-nerve palsy. Analysis of 100 cases. Arch Neurol. 1996 Jun;53(6):561-6. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550060105023. PMID: 8660159.

- Turgut S, Turgut M, Atasoy E. Bilateral hypoglossal nerve injury following head trauma. J Trauma. 2005;59(6):1470-1473.

- Finsterer J, Grisold W. Disorders of the lower cranial nerves. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2015 Jul-Sep;6(3):377-91. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.158768. PMID: 26167022; PMCID: PMC4481793.

- Sanders RD. The management of neuropraxia of the recurrent laryngeal nerve and hypoglossal nerve during carotid endarterectomy. Am Surg. 2002;68(5):456-459.

- Yamamoto T, Yamasoba T. Isolated hypoglossal nerve palsy: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. J Neurol Sci. 2008;264(1-2):191-196.

- Massey EW. Isolated hypoglossal nerve palsy in a karate player. JAMA. 1981;246(22):2587.

Content Alerts

SignUp to our

Content alerts.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.